80 knot headwind?

On April 14th I was sitting on the ground at Dickson TN as a cold front moved through, bringing thunderstorm cells and lightning and some serious downpours with it. I knew if I waited a few hours, it would be gone and the only thing between me and my home base of KTRL near Dallas would be light rain, IMC, and very strong headwinds.

The forecast was for 40 knot headwinds. I was not looking forward to my 2.5 hour flight turning into 3 hours, but I was willing to accept it as a necessary evil.

I filed my IFR flight plan, got my clearance, and took off into the clouds, climbing to my cruising altitude of 8000 feet in mist and light rain. The ground was sort of visible below, but water streaked the windscreen.

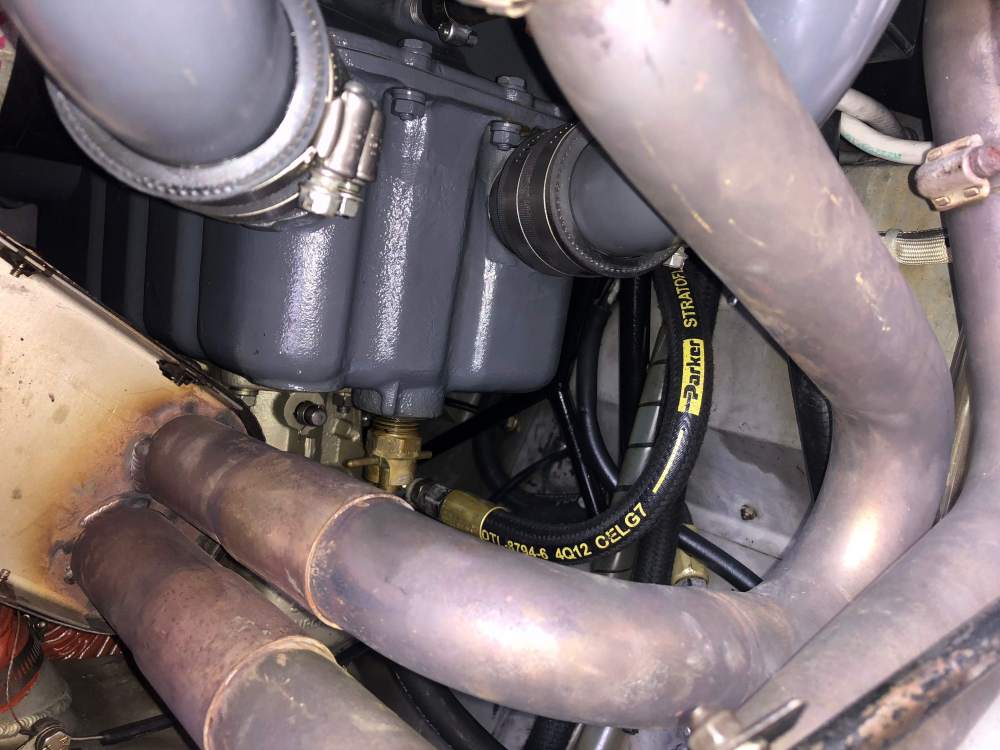

(I should mention here that I can hear you saying "you dork, why not fly at 4000 feet and take a 20 kt reduction in headwind?" My answer is that my M20A doesn't like to fly that low. It produces > 200 degree differences in EGT between cylinders because of the lousy job Lycoming did designing the intakes, and that sets off my EI engine monitor alarm. I never fly that low.)

So upon reaching cruising altitude, trimming everything up, and leaning, I settled in for my 3 hour leg to KSUZ outside of Little Rock. And I started watching my ground speed to see if the 40kt predictions were correct.

But instead of seeing something like 105 kts of groundspeed, I was seeing 90, then 80 knots. Then 70 knots. My GPS was telling me it would be 3 and a half hours flying time. I was getting more and more amazed at the hellacious headwinds.

Then my Bitchin' Betty voice annunciator interrupted me as she spoke into my headset "Check Engine Analyzer". I quickly glanced at the engine analyzer and noticed that the #3 cylinder was running over 200 degrees richer than the rest. I tweaked the mixture control, but it didn't make much difference. "Check Engine Analyzer" she said again.

At this point I looked at the manifold pressure gauge. Wow, 15 inches. The airspeed indicator said 115mph. Ground speed was down to 65mph. Hey wait a minute, I should be seeing a lot higher indicated airspeed and MP at 8000 feet. I quickly concluded there was something wrong with cylinder #3 and that was robbing my engine of power.

This was not an 80 knot headwind. This was an engine problem!

Many of us learned to fly in a Cessna 152. I still remember how the approach to landing power reduction was drilled into my head by my CFI, Bill Riggins, in 1983:

Abeam the numbers, pull carb heat, reduce throttle to 1500 RPM, hold altitude until the airspeed drops inside the white arc, then lower one notch of flaps. Yada yada.

When I started transition training in my M20A, my instructors told me I will rarely ever need carb heat during approach to landing. And indeed, in 12 years of flying, I have never needed carb heat.

But I remembered someone saying, if you're having difficulty in a carbureted Mooney getting the cylinders to have a more balanced mixture, try adding carb heat.

So I did. And I watched the manifold pressure climb. 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. And the airspeed climbed. And the groundspeed climbed. And the #3 cylinder EGT rose.

I looked at the outside air temperature gauge. 56 degrees. Couldn't be carb ice. Could it? I turned off the carb heat and watched the engine power slowly begin to drop. 19", 18", 17". OK, carb heat it is. I flew with carb heat on until I popped out of the clouds. At that point, I tested carb heat and found it wasn't needed anymore, and I continued my flight as usual.

Greg Ellis reminded me of the graph showing severe carb icing possible from 25 degrees to 60 degrees with humidity levels around 75-100%. I was in probably 100% humidity at 56 degrees OAT, so very much in the danger zone. I'm not used to needing carb heat at cruise power settings, but in IMC in that temperature range, it may be worth thinking about this a lot more frequently in flight.

A friend of mine crashed and burned in his Pietenpol in Florida because of carb ice. In Florida. It can happen anywhere if the conditions inside the venturi are suitable for ice formation. In this case it happened fairly slowly, but I suppose it could also be much more abrupt.

"Take heed of thine airspeed, lest the ground rise up and smite thee. And take heed of thine dewpoint, lest the carb ice up and smite thee!"