-

Posts

1,535 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

5

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Gallery

Downloads

Events

Store

Everything posted by Vance Harral

-

IO-360-A1A engine driven fuel pump options

Vance Harral replied to Vance Harral's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

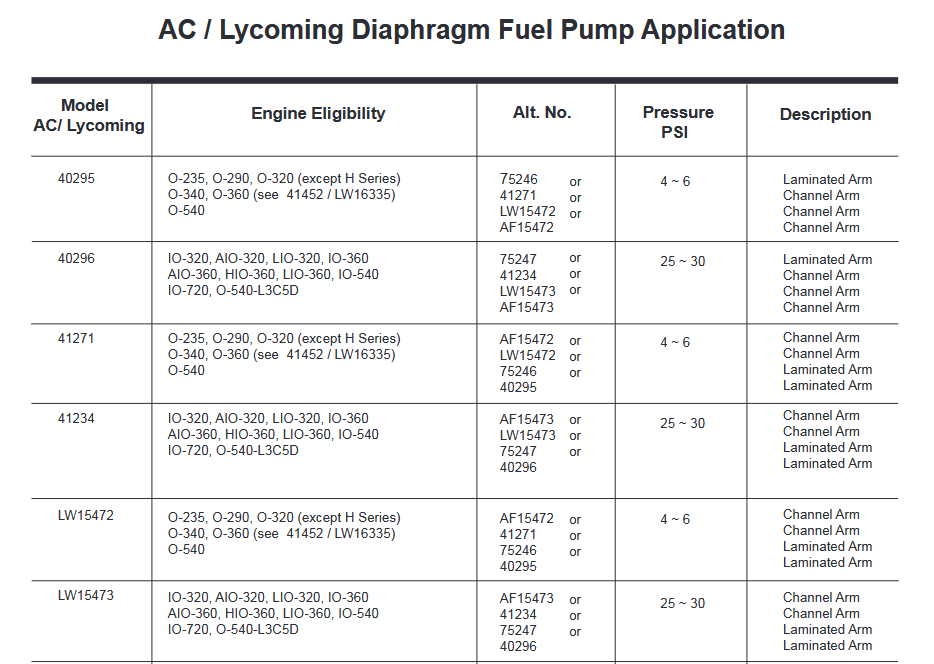

That's certainly a definitive reference, but the Tempest guide says thusly: Another Tempest document has this data, in which the 41234, 40269, and LW15473 are seem to be listed as alternates for each other, albeit with "Channel Arm" vs. "Laminated Arm", whatever that means. -

IO-360-A1A engine driven fuel pump options

Vance Harral replied to Vance Harral's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

Thanks very much for the pointer to that thread, @takair. It's regrettably disappointing in two respects. One, it doesn't seem to answer the questions of whether an LW15473 that produces over 30psi is actually mechanically problematic, vs. only legally problematic, and how/if one can ensure getting a unit that doesn't exceed the legal spec. Two, it documents that the cost of the pumps has nearly doubled in the last 3 years. Aside from pressure regulation, I'd still like to understand what's supposedly better about the LW15473 that justifies a higher price, given that the other flavors are readily available. -

Finished a flight yesterday and observed fuel dripping from one of the hoses that exits the left side cowl flap (not from aux pump drain, that's further back). As the "streaming" blue stain on the nose gear door in the attached photo shows, there's evidence it dribbled in flight and streamed back along the gear door (there's a little oil there too, but that's normal for us). Haven't uncowled the engine yet, but I'm 99% sure from memory this is the hose that goes to the engine-driven fuel pump's overboard drain. As I understand it, this means the internal seals and/or diaphragm of the pump are failing, and it's time for a new or overhauled unit. My question to the hive mind is about part numbers. The application guide at https://www.aircraftspruce.com/catalog/pdf/TEMPEST-FP-APP-LYC.pdf has three options for the fuel pump in an IO-360-A1A, part numbers 41234, 40296, and LW15473. Researching these part numbers suggests variations involving "channel arm", "laminated arm" and "dual diaphragm". Anyone care to render opinions on why we should choose one part number over another? All three flavors appear to be readily available in new and overhauled forms. Some are more expensive than others. The cost difference isn't an issue for us, but I want to understand the pros and cons before engaging with our mechanic.

-

Non-Towered Pattern Entry from Upwind Side (Poll)

Vance Harral replied to 201er's topic in General Mooney Talk

Phoenix is certainly busy, but screenshots like this are misleading and create more anxiety than necessary. Let's conservatively guess there are about 200 aircraft in that screenshot. But they're spread out across the entirely of the Phoenix TAC chart, which is about 6800 nm^2. The traffic icons in that shot depict airplanes with wingspans of about 3 miles - ridiculously over-scaled. Fun to show, maybe, but not meaningful. Apologies if that sounds snarky, but it triggers one of my pet peeves, which is a few clients that are completely fixated on traffic. If they don't see anything on their traffic display at 5 miles, they keep zooming out until they do, then they start worrying about a "threat" that's 20 miles away while ignoring other, more important risks. Like, you know, actually flying the airplane. -

Pilot safety is best enhanced by focusing training on the types of operations the pilot actually flies. Sounds like for you, that's a lot of IFR (not necessarily IMC) to busy, towered airports. Other pilots really enjoy flying circuits, working on smooth, precision touchdowns at less busy, uncontrolled airports where they can do a lot of them. Neither mission is more or less important than the other. There's a natural assumption that owners of "traveling airplanes" are largely in the first set, but I haven't actually found that to be true. In my work as an instructor, I've run across plenty of Mooney/Beech/182/etc. owners who just like making $100 hamburger runs to the same set of nearby, non-towered airports. Sometimes they'll contact me for training on getting in and out of Big City Tower because they don't do it very often. But when I follow up after an initial lesson, some of them decide on the basis of the experience that they just don't want to do that, because it's not fun and isn't mission critical to them. This is actually one of the most complicated things about being an instructor. I get contacted by a lot of clients who want training on "Thing X" (towered airports, instrument procedures, slow flight and stalls, whatever). But you have to understand their motivation to serve them: do they actually want to do Thing X and need confidence, or have they been convinced by peer pressure they should be good at Thing X despite not actually wanting to do it? This is complicated in part because Thing X might be fundamentally important (i.e. likely to cause an accident), or they may be afraid of Thing X but discover they actually like it once they get used to it. So to address your question directly, I'd gently suggest it's somewhat meaningless. There is nothing magic about a Mooney that makes a standard traffic pattern typical or atypical. It's about the pilot, not the airplane.

-

For a lot of people, aircraft ownership is effectively a social club in addition to actually using the thing. They like hanging out at the airport FBO or cafe, watching students work the traffic pattern, eating doughnuts and chewing the fat at the hangar owners meetings, etc. Sure, they could do those things without owning an airplane, but ownership gives it a certain weight and cache'. Then as folks age, it's often more and more difficult to go flying for a number of reasons, while the cost and time sink of keeping the airplane airworthy increases. But if you give up on the flying and the airworthiness, the cost of staying in the social club becomes mostly fixed, relatively small, and is already baked into the retirement budget. Every "club" has members like this, e.g. people who drive their golf cart to the 19th hole cafe every other day but haven't played a round in years. People who are still flying find this sad, and lament seeing formerly airworthy airplanes rot on the ramp, with all purchase and partnership offers rejected. To the extent you think of an airplane as a living object to be loved, I get it. But in reality, it's just a machine, and it's really no one's place to tell the owner different as long as they're keeping up with hangar/tie down fees and taxes It's no more or less sad than Grandma's mostly unused fine china ultimately going in the dumpster, or being sold for a dollar a plate at an estate sale.

-

Where to move OAT sensor to?

Vance Harral replied to AndreiC's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

Just get some type K thermocouple wire (https://www.aircraftspruce.com/catalog/inpages/jpiktypewire.php) and extend the wire as needed to locate the probe in the best location, which is under the wing (out of sunlight) and well outboard of the exhaust. Sometimes people are reluctant to extend thermocouple wire because they've heard that doing so might be a problem. There is a grain of truth to that, but only for very old gauges and/or extraordinarily long wires. Modern temperature measuring instruments (even 1980s "modern") are designed to accommodate any reasonable length of thermocouple wire between the probe and the instrument. Regarding the splices, thermocouple wire is difficult to solder, but you can use conventional barrel crimps or any other kind of mechanical connector. I like these ones: https://www.aircraftspruce.com/catalog/inpages/eioverlapolc-1-10-05470.php. They are an EI product, but they will work fine with your JPI system. -

I've seen this movie dozens of times in my career. The words that come out of the developer(s) mouth are "It doesn't need a manual". But you need to understand this for what it really is, which is, "I don't like writing manuals, so I'm just not going to do it." For better or worse, the industry accepts this, mainly because software is almost entirely developed and managed by people with skill sets that don't include great written communication. It's telling that In decades of doing this work, I have literally never seen someone financially rewarded for excellent documentation, or scolded/put on a PIP/whatever for poor documentation. A few projects put in the work somehow, Foreflight being one example. There have also been interesting efforts toward "The code is the documentation", e.g. Literate Programming and tools that support it. These things tend to fail because actually making use of them is even more effort than just writing the documentation conventionally, and developers already don't want to do the latter. It's possible LLMs might make this better, but I'm not holding my breath.

-

We're getting pretty far off topic, but, I'll bite. Why do you think open source has *clearly* "won" over closed-source projects? In your response, I hope you'll take a crack at explaining why the following cases are all anomalies that don't count, despite the open source community having decades of opportunity: Why is social media and messaging dominated by commercial platforms like Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp? Why haven't things like Diaspora displaced them (pun intended)? Adobe Photoshop dominates the image manipulation market, Why hasn't GIMP won significant market share, despite having 30 years to do so? Commercial POS/CRM/payroll/accounting software is unquestionably dominated by closed-source commercial software: QuickBooks, Peoplesoft, Salesforce, etc. GnuCash has hundreds of contributors but is essentially unheard of in these circles. Why? (my niche) Verilog RTL simulation is dominated by commercial products: Xcelium, Questa, VCS. The open source simulators don't scale, are consistently behind the latest IEEE standards, and are only good for toy projects. If open source has clearly "won", what happened here? The examples above suggest otherwise. My guess is you don't actually have any data about what percentage of "mission critical" systems are powered by open source software, but let me know if I'm mistaken. In thinking about that, make sure you consider the entire system stack. Just because Linux is at the bottom of it doesn't make it an open-source project. Agile is a reasonably successful software management approach, but it's use has nothing to do with whether a project is open source or not. Every commercial software vendor I've worked for in the last decade has implemented (or at least claimed to implement) "Agile" techniques. One of the most famous companies using short release cycles, a.k.a "move fast and break things" is Facebook; and while a lot of the underlying components of that software stack are open source, the product itself is most decidedly not. Out of curiosity, have you actually read The Cathedral and the Bazaar? The canonical principles in that seminal document about Agile-ish things don't actually have much to do with whether the software is open-sourced or not, that's just the environment where the experiment took place. In summary, I think you've got a serious blind spot about open source always "winning". Your explanation of why an open-source EFB isn't dominating the market is a good example of that. The fact the software might have to comply with regulatory standards isn't some sort of strange corner case problem that's an inherent barrier to being open-sourced. It's just another product requirement. Albeit one that isn't "sexy" and therefore - like so many other things - maybe not attractive to volunteer-ish labor.

-

Then why isn't an open source EFB already the market leader? It's not like open source is some radical new idea as it was decades ago, nor is the concept of an EFB new, nor is there any particular technical barrier to AvareX and other EFB projects - they've got the same access to IDEs and app stores as Foreflight and Garmin. Any thoughts on why WingX has faded into obscurity, despite having the supposed advantage of lacking huge, corporate bloat? I'd be happy to use a well-supported open source EFB, but the fact there have been a number of really successful open source products doesn't mean open source is an automatic panacea. Open source projects are successful when they have a strong leader and a well-designed test and support system, staffed by people interested in test, support, and documentation. The main reason Linux was so successful is that Linus himself provided significant guidance (much of the effort ultimately wound up involving infrastructure, not coding the kernel). Most of the people working on open source aren't actually interested in that un-sexy stuff, so most open source projects fail to sustain themselves. That doesn't make open source bad or inferior, it just makes it "not magic". And these problems are actually getting worse, because at this point the majority of open source projects are staffed by very junior developers - college students or "boot camp" kiddies - who are simply trying to build a resume and a body of work on GitHub to get hired for paid work. There's nothing wrong with that, and it can result in great work, but it requires guidance from people with software management experience. Again, you don't get a good product simply by having "motivated programmers", that's only part of the required skill set. There's a lot of other important stuff that's not sexy, and you usually have to compensate people to get them to do it. Saying "open source EFBs will win because Linux won" again suggests you don't really understand the reality of software development in 2025. I don't understand this "zinger" at all. The iPhone and iPod were huge projects undertaking by a commercial organization with a profit motive, staffed by hundreds of personnel performing project management, verification staff, support teams, and so forth. A significant amount of the work that made those products successful was the development of the Xcode IDE, the infrastructure associated with the app store, collaboration with cellphone providers, marketing, and so forth. The idea that those products were successful because of a few really good software engineers is laughable.

-

That has been true for most of the history of software development, but is a lot less true today. Between offshoring and AI code generation, software development is being rapidly commoditized. The quality of the resultant software is about what you'd expect, but that's not going to stem the tide. Software in general - including EFB software, will almost certainly follow the same path as airline service, culminating in almost unbelievably inexpensive products, that are incredibly annoying to use.

-

This statement suggests you don't have any experience managing large-scale software development. The most likely outcome of getting a team of 10 - or worse yet a hundred - "motivated software developer pilots" is completely unusable chaos. Yes, there are any number of free EFBs that are reasonably functional, because lots of people have the same idea as you. A single developer can actually turn out something mildly usable in not too much time. But as features are added, the things that make something as complicated as an EFB actually usable, include interface design (which is *not* coding), a very robust verification environment, documentation, and user support. The vast majority of "motivated software developers" are terrible at these things. Ask me how I know. There is a good reason that the vast majority of EFB users choose a paid product backed by a large company.

-

Ironically, this statement also indicates a fundamental misunderstanding of operational principles. Voltage is not current. How many amps might have flowed from AUX to ground in this mis-wired installation depends on the load through the complete circuit, as well as the ability of the center point of the stator wye to actually supply current. It is extremely unlikely that 50 amps of current every flowed in the circuit, the "burning smell" Grant describes not withstanding. @PT20J says above this is a "low current" output. Not sure how he knows that, but there is no one on the forum better informed about the movement of electrons than him. The thread you linked to above is mine, and my mechanic made exactly the same mistake as Grant's. Your own confusion about the operational principles, as well as mine (I am a degreed electrical engineer), as well as an identical mistake by two entirely separate mechanics, and the presence of multiple threads asking how all this works, means that the problem is the design and documentation of the system rather than the humans maintaining it. It is apparently impossible to find a manual specific to the Hartzell ALY-8520 (I had the same trouble doing so as Grant). Said alternator relies on a case ground which is not shown in the Mooney schematics because it's "implicit", but this is easily confused with the shield termination for the shielded wires in the system. The Mooney schematics also just ignore the presence of an AUX terminal on the alternator rather than explicitly marking it N/C, which is counter to good design principles. So what we have here is actually bad design/documentation, and it's no wonder that even well-trained, competent people are confused by the system. The mistake by Grant's mechanic is entirely forgivable, and accusations of incompetence in making it are weak. For what it's worth, our airplane was ground run for several minutes in the mis-wired configuration with the AUX terminal grounded. Once this mistake was corrected, the alternator began operating normally, and has continued to do so for the entire 5 years and several hundred flight hours since I made my post. I can't say whether Grant's alternator may or may not have been damaged internally, but my own experience shows that this mistake is not necessarily immediately catastrophic.

-

Thanks, that's great news.

-

FYI, it's my understanding that Dan is no longer with LASAR. I'd be happy to be wrong about that if someone wants to correct me.

-

What kind of clouds do you refuse to enter? Poll

Vance Harral replied to 201er's topic in General Mooney Talk

Well, here's a real-time clip of what it looks like for me right now on an old Windows 10 laptop with 2.4 GHz WiFi and cable internet. Pretty snappy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kpPWpbeezz4 -

What kind of clouds do you refuse to enter? Poll

Vance Harral replied to 201er's topic in General Mooney Talk

Huh. I don't get that behavior at all, nor do a few others I've recommended the site to. Just tried it on my phone and it's snappy there too. May be specific to your combination of computer/browser/internet. But not accusing you of fibbing. I can tell just by the look of the thing that it's a resource intensive interface. I really liked the old rucsoundings.noaa.gov site. Kind of an old-fashioned interface, which is I suspect why they took it down. But it was simple to use. -

What kind of clouds do you refuse to enter? Poll

Vance Harral replied to 201er's topic in General Mooney Talk

FYI, https://sites.gsl.noaa.gov/desi/ seems to be the NOAA replacement for rucsoundings.noaa.gov. It didn't show up until a while after rucsoundings.noaa.gov disappeared, and it's not well advertised. But it looks to be an improved version of the same interface. Navigate to the site, then click the icon in the top right corner that looks like a little Skew-T plot. That will show you a plot near your geographical location, and from there you can select different locations and times. Once you've selected your favorite site, you can bookmark the lengthy URL that shows up in your browser and use the bookmark to navigate directly there the next time. -

Restore or remove Accu-Trak B11

Vance Harral replied to christaylor302's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

We have a fully working Brittain PC/B-5 system, and it's nice for what it is (75-year-old technology). But at this point, I think the question of resurrecting a non-working Brittain system has less to do with cost and workload - which are manageable - and more to do with the availability of mundane parts: vacuum lines, servo boots, etc. http://www.brittainautopilots.com/ is still online with a listed phone number, but it's my understanding that people who have recently tried to obtain parts either never get a response, or get a response that the company is "in limbo" with little or no legal ability to actually make parts. That leaves salvage items, kludge fixes, and under-the-table deals, which is a frustrating scenario for an aircraft owner. It is not difficult to debug why the system isn't working, but once you identify the problem(s), you may find it difficult to resolve them in a satisfactory manner. In our case, we have a small cache of spares, but maintaining the system has begun to feel more like maintaining a warbird than a certified airplane. -

Looking for RH brake pedals '77 M20J

Vance Harral replied to David M20J's topic in Modern Mooney Discussion

No, that's something I just wouldn't do - too much risk. In my case, it's easy to avoid that risk because I have instruction privileges at a local flight school. I can take anyone who is a truly green newbie over to the flight school and put them in the left seat of a 172, which is frankly a better Discovery Flight platform anyway. Over the course of a few flights at the flight school, I might build enough trust with them to get into a different airplane with only one set of brakes. But there is a lot more to that conversation than just the brakes, see below. This is a little awkwardly worded, not sure what you're asking here. I wouldn't hesitate to give instruction in a non-dual-brake Mooney to someone who already held a Private Pilot license. At that point it's reasonable to assume basic competency with the brakes, along with an understanding of the (rare) conditions under which they're needed. It's just transition training, a very common and reasonable operation. If you're talking about a student who is a post-solo but pre-private pilot, transitioning to a Mooney for the remainder of their training, whether or not the Mooney had dual brakes is the least interesting question about such a proposition. I'm not a naysayer about this sort of thing. One can absolutely train for the Private Pilot certificate in a Mooney, and in fact I'm familiar with a person who successfully earned his Private Pilot certificate in a turbo Mooney. But I declined to be involved with that operation for a couple of reasons. One is that it predictably took them a very long time to finish, working in fits and starts. It wound up being a multi-year effort, and to be honest that just didn't sound like any fun to me. More importantly, this person did all their training "naked", because they couldn't find anyone to insure the operation of a turbo Mooney by a student pilot. Even though I carry my own liability insurance for instruction in owner-flown aircraft, the details and dollar amounts just got too far above my comfort level, so I recommended they seek out someone else. Which they did. Another instructor I knew casually took on the training gig, and succeeded. Based on observing their success over time, I did agree to give the student a single "mock check ride" right before their practical test. But at that point, whether the aircraft had dual brakes (I don't even remember at this point) was irrelevant. A J model is less complicated than a K, and perhaps more reasonable for primary training. But I have no idea what the current insurance market looks like for that sort of thing. And whether I would take on such a gig would depend more on the person than on the airplane. In addition to physical and financial risk, I care about the likelihood of success, and whether it's going to be any fun for both of us; and training in an airplane that's not a trainer weighs on those goals to some degree, even if you think Mooneys are cool. I think people who point out in these sorts of threads that the military solos people in an 1100shp complex turbines, inappropriately gloss over the fact that doing so is a full time job for both instructor and student. Most civilian aircraft training is a weekend/afternoon hobby, and it doesn't take much additional overhead to make the hill of success too high to climb. -

Problem with Misc. Field displayed on my GI275/HSI

Vance Harral replied to NicoN's topic in Avionics/Panel Discussion

Sounds like a firmware update is the next thing to try if you're not on the latest version. Can't offer you much more in the way of suggestions - we're just lowly G5 consumers, I haven't tried to follow the GI-275 firmware versions. I'm not in the avionics business, but I am in the electronics business, and I have at least some sympathy for Garmin wanting most of their service business to work through shops with which they have an established relationship. Things do tend to go better that way for a collection of reasons. But anyone in this sort of business also understands that granting "authorized dealer" status doesn't make that specific shop a good resource vs. a skilled DIYer. Sorry you had a a mediocre experience with your last Garmin shop, but it's not particularly surprising. I recently had a bad experience with a "Mooney Service Center", so I feel your frustration. -

+20 year old donuts (1966 M20E)

Vance Harral replied to Matt Ward's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

True, but the thing that's killing people at the greatest rate has nothing to do with shock disks, or mechanical condition in general. The vast majority of maiming and death in the airplane world remains poor pilot technique (including me, I'm not immune). It would be an interesting world if people spent most of their "safety dollars" on actually flying the airplane and getting coaching from other experienced pilots (doesn't necessarily have to be an instructor). In the real world, $2400 shock disks often lead to less flying - particularly training - and that's a much higher risk than the condition of the shock disks themselves. That's my problem with this whole, "It costs what it costs." philosophy. No one's pocketbook is unlimited, but even if it was, safety isn't simply a function of maximizing how much time and money you spend on the mechanical maintenance of your airframe. -

Problem with Misc. Field displayed on my GI275/HSI

Vance Harral replied to NicoN's topic in Avionics/Panel Discussion

OK, the video makes it easier to understand your question. I'm not a GI-275 expert, but based on general principles I have two guesses. One is that it's a software issue as you speculate: either a bug, or a config setting that is so esoteric and convoluted it may as well be a bug. That seems the most likely cause, but you'd have to check with Garmin on that. My wild conspiracy theory involves the inputs an air data computer needs to compute winds aloft. Those are pitot pressure, static pressure, OAT, ground track, and ground velocity. To the best of my knowledge, each GI-275 receives these inputs "directly", meaning the HSI does not rely on the PFD to transmit them, but rather that it has it's own independent inputs (albeit ones which may be connected in parallel to the PFD). In the GI-275, the pitot and static pressure inputs come from actual pitot and static lines connected to the instrument. Everything else is electronic wiring. It's somewhat unlikely the electronic wiring of your HSI is compromised, as that's "all or nothing" data that would likely cause other problems you probably would have noticed. But I'm wondering if it's possible the pitot and/or static lines are slightly loose or slightly clogged, such that the air pressure data received by your HSI is erratic in a way that might cause certain air data functions to "go offline", particularly at low speed (i.e. on the ground). This would require a situation where the pressure lines are good enough not to generate red Xs, but not good enough for whatever code computes winds aloft. Seems very unlikely, but an easy experiment is to pull the breaker on the PFD in flight (on a good VFR day, obviously), and let the HSI revert to being a PFD. Then you can see if the airspeed an altitude on that unit are erratic in any way. If so, you might check the pitot and static connections to it. -

+20 year old donuts (1966 M20E)

Vance Harral replied to Matt Ward's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

If you read back through this thread, you'll see that @Gert did exactly that for his own purposes, and tried to help out other owners by making parts available at https://avunlimited.co/product/mooney-landing-gear-shock-disk/ There was some predictable skepticism about the degree to which this qualified as OPP, but I think most of the group here was enthusiastic and supportive. Response elsewhere (Facebook posts) was less kind. The parts on that web site have been listed as "out of stock" for years, and Gert hasn't visited this board in 3 years. I don't know what all may have gone on in the interim, but it renders me pessimistic that there's an OPP solution for the masses. Only, perhaps, one-off installations by individuals who stay quiet about it. -

+20 year old donuts (1966 M20E)

Vance Harral replied to Matt Ward's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

Correct. But the fix for that costs pennies in the way of O-rings, hydraulic fluid, and air; and it doesn't require special tools most shops don't have. Mooney "pucks" were a fine idea in their time, but the current state of the parts and service market makes them undesirable. Bonanza/Commanche/etc. owners aren't contemplating whether they should jack their aircraft up off the gear after every flight. Buy them now. They have a decent shelf life when stored indoors, uninstalled; and the price and availability are only going to get worse between now and when you need them.