-

Posts

1,496 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

5

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Gallery

Downloads

Media Demo

Events

Everything posted by Vance Harral

-

As someone who also lost one of these cover panels in flight, I concur. When we got the airplane back home after our event, we worked with our mechanic to install rivnuts in the fuselage, to receive the screws that hold these panels on. Signed off as a minor mod. Much more secure than the "screw only" technique, and no issues with loose screws or loss of panel in the 10+ years since.

-

Off-field emergency landing - gear up? gear down?

Vance Harral replied to AJ88V's topic in General Mooney Talk

Other things have so much more influence on survivability in a forced landing, that the position of the gear at the moment of touchdown is not worth worrying about. If you have time to devote to thinking about off-airport landings, you should be spending the mental energy (and training) on those other concerns - most notably glide performance, precision landings, and touching down at the slowest possible speed. The only semi-scientific look at gear position in forced landings I'm aware of, studied ditching in the "soft surface" of water. But the data there showed no evidence that landing gear position mattered: http://www.equipped.org/ditchingmyths.htm I have no idea where this persistent myth comes from, it strikes me as lazy thinking. First, no real-life airplane has a "nice flat bottom". The average M20C has a chunky "chin" which holds the air filter, bulbous nose gear doors, various antennas, flap hinges, sometimes-non-retractable steps, imperfectly rigged gear doors, tie-down rings that were not removed for flight, and other protrusions that stick out and can catch things. Yes, all those things tend to slide if you set down on pavement, but soft ground is a different story. More importantly, Mooneys have relatively low-dihedral wings. Catching a wingtip instead of "sliding on the belly" is a high-G deceleration event that places occupants at significant risk; and it will occur with only a slightly-less-than-perfect roll attitude on touchdown, and/or with just the smallest amount of surface variation (row furrows, rocks, dirt clods, vegetation, etc). The likelihood of digging in a wingtip is even higher given that your "not perfectly smooth bottom" is likely to impart a certain amount of rolling motion on impact. No, I don't have NTSB data on this, but I do have a lifetime of bellying in model airplanes with no landing gear (and much smoother bottoms) on grass, and it often doesn't go the way you hope - in particular, I've seen plenty of flip-overs. So whatever you're afraid of "catching" the landing gear on may be an actual threat, but you're at least as likely to catch a wingtip on that same threat as you are the gear; and if you do, you'll get a sideways slewing motion that most aircraft seat belts are not designed to guard against. This goes for mild sea swells as well as plowed field furrows, hence the data on ditching that gear position doesn't matter. My opinion - which is worth what you're paying for it - spend less time thinking about gear position and the direction of furrows; more time on making the field in the first place, and arriving there with wings level and minimum energy. My experience with power-off 180s (both teaching them, and my own ineptitude) suggest to me that most of us are terrible at this. Accordingly, the only value in worrying about aircraft configuration is with respect to arriving at the intended touchdown point with minimum energy. Anything else is like worrying about whether you should roll the windows up or down on your car, as you're driving over a cliff. -

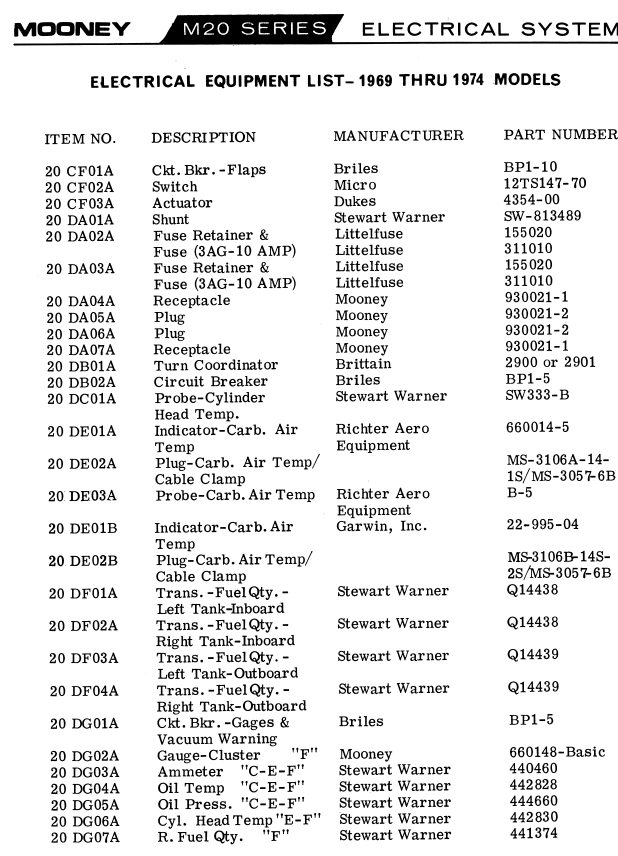

Electronic parts are well documented, but again, in the Service Manual rather than the IPC. The image below is pasted from my service manual. The "Item No." corresponds to labels on the schematics. The catch is that a lot of these parts have been superceded by other parts, so knowing the original manufacturer and part number is often only the beginning of the story for finding replacements.

-

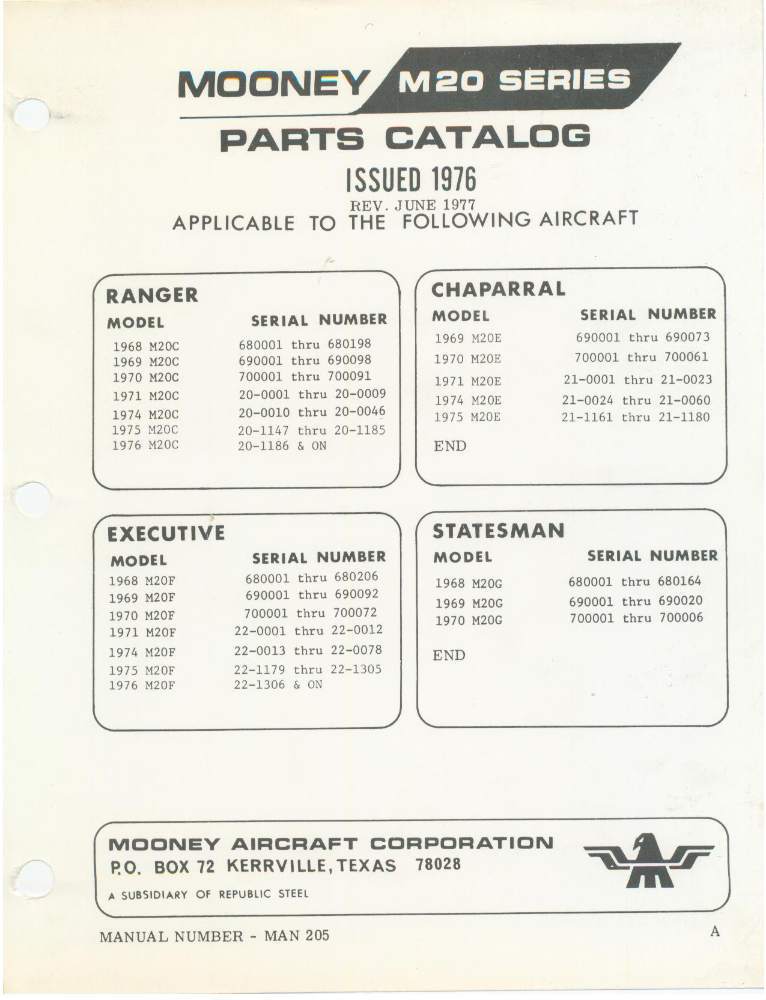

Part numbers are contained in the Illustrated Parts Catalog for your airframe, I've attached an image of the first page of my paper copy. Scans of paper images are so last-century, though. There are IPC PDFs floating around from a decade or so back, that Mooney created, and that's probably what you want. If you don't find it in the downloads section of Mooneyspace or someone doesn't send you a copy, I'll try to find mine. Having said that, electronic parts such as the switches are an exception. The electrical system of the airplane - including parts numbers - is actually found in the service manual, not the Illustrated Parts Catalog.

-

This is clever, and not something I'd thought of. But Foreflight now allows you to add VFR pattern entries to a flight plan, and I'm betting almost everyone who wants electronic guidance for a VFR pattern prefers that to OBS mode.

-

Here's a somewhat esoteric one: I know how to use OBS mode on the GNS/GTN series. This is the mode where you use the OBS knob on your CDI/HSI to select a course to/from the currently active GPS waypoint, and the CDI/HSI depicts needles relative to that course. In other words, it makes the active waypoint work like a VOR. Hard to argue there's much use for this anymore, but it's kind of a fun trick.

-

Engine management for commercial maneuvers

Vance Harral replied to Nico1's topic in General Mooney Talk

I also fly a 1976 Mooney M20F, which we bought 20 years ago in a partnership, and have put nearly 2000 hours on the engine with no trouble. It's not a flight school trainer, but it's been used by several of the partners to train for and obtain commercial certificates, across all seasons of the year, and we continue to fly the commercial maneuvers for proficiency on a regular basis. Bottom line: you're way overthinking this, don't worry so much about it. Specifically do not worry about rates of heating or cooling. It's just not a thing for this engine, in the flight regime where normally aspirated piston singles fly. If you're repeatedly flying a large number of high-power/low airspeed maneuvers in the heat of summer (power on stalls, chandelles), check the CHT every few minutes. If they get over 380, sure, you can level off at cruise speed and open the cowl flaps a few minutes. But that's it. Otherwise, you're not going to hurt your engine with any of the commercial maneuvers. You're generating more wear with a single startup/taxi/takeoff/climbout sequence than you do in hours of commercial maneuver training. -

This guy is an embarrassment to Mooney pilots.

Vance Harral replied to Brandt's topic in Mooney Safety & Accident Discussion

Sure, different opinions make the world go round. But what you should be asking yourself is why, collectively, pilots are dying and getting into legal trouble at roughly the same rate as in the past. That's what the accident data says. I get that everyone feels better with new tech, but that's not really the goal, is it? -

This guy is an embarrassment to Mooney pilots.

Vance Harral replied to Brandt's topic in Mooney Safety & Accident Discussion

There's more to navigation than following a straight line between present position and destination. Terrain and airspace avoidance are two complexities that come to mind, even under VFR. Old tech was a paper map that was challenging to use because it had to depict everything statically and use subtle visual techniques such as "vignette"; and VOR nav that required tuning frequencies and understanding a CDI. Foreflight tech is a dynamic moving map in which terrain and airspace are layers that can be enabled (or not if you don't know it's a layer feature), or disabled (including accidentally); and proximity alerts that may or may not be enabled on the screen and/or through your headset. Both technologies require setup, and the SA to know you're near terrain/airspace of concern in the first place so you know to pay a little extra attention to the nav. Based on having taught students with both technologies, proper terrain and airspace navigation feels like six of one, half dozen of another to me. Right. And the pink line on Foreflight can suddenly go away with something as simple as an errant tap, it doesn't require equipment failure or GPS hacking. More importantly, if you're part of the new tech crowd that deliberately turns off the sectional overlay in Foreflight because the dynamic Aeronautical map is better, it's as easy to accidentally turn off airspace and terrain layers as it is to follow the pink line, and then you have absolutely no airspace or terrain data at all. To be clear, I absolutely agree that navigation is much easier in the modern era when everything is working. I'm just emphasizing that "working" isn't only about equipment failures, it's also about setting up the equipment. And equipment setup is more complex in the modern era than it was in the past. Accordingly, I'm not too surprised we don't do much better now than we did back in the day. We unquestionably have better capability, but for whatever reasons, it's just not translating to better performance. -

This guy is an embarrassment to Mooney pilots.

Vance Harral replied to Brandt's topic in Mooney Safety & Accident Discussion

This statement oversimplifies the challenge. What if the technology is operating exactly as designed, but not the way the pilot expects? Is that “working” or not? Modern technology is a lot more capable, but also a lot more likely to be in this “What’s it doing now?” state. -

ALT LOW VOLTS bus breaker keeps popping

Vance Harral replied to warrenehc's topic in General Mooney Talk

That's not the original panel in from a 67F, so it seems this airplane has custom avionics. I have factory schematics for various vintages of the M20F, but I'm not seeing any circuit breakers in them labeled ALT LOW VOLTS. Avionics shops are supposed to provide the customer with new schematics when a major change like this is made, but the shops almost never do that. So... just a guess... ALT LOW VOLTS doesn't strike me as having anything to do with the alternator itself. Rather, I'm guessing that breaker (it's a circuit breaker, not a fuse) powers a system that lights a warning light and/or sounds a buzzer, when bus voltage falls below what the voltage regulator is trying to hold. Do you have a "LOW VOLTAGE" light in your panel? If so, it's probably powered by that breaker, and won't work if the breaker is tripped. The light may be failing in a way that is causing high current, and therefore causing the breaker to trip. It's also possible the breaker itself is just worn out and is tripping even though the current it's carrying is normal - this does happen on occasion. Suggest you check the bulbs and/or wiring associated with your LOW VOLTAGE light/buzzer, if you have one. But again, this is all just a guess. -

I'm sure I haven't performed/coached as many stalls in Mooneys as @donkaye, but I've done many, including - though I know Don will scold me for this - cross-controlled stalls for CFI training in my own M20F and a friend's 252. Based on that experience, and the stories I read here every time this comes up, I'm convinced the Mooney wing isn't less-well-behaved in a stall than others, as designed; but that it's less forgiving of mis-rigging and minor "dings" than other airframes. Lots of us report benign experiences with power on, power off, accelerated, and cross-controlled stalls in varying M20 airframes. All the stalls I've ever encountered in the M20 platform - including those cross-controlled stalls - have been benign. It's true that in a skidding stall, the airplane will roll - as expected - toward the wing that is already lowered, and therefore can seem like quite the E-ticket ride if you don't know what to expect. But with reasonably prompt forward yoke, neutral ailerons (don't pick up the low wing with aileron input!), and rudder correction, neither is it particularly "scary". Having said that, I certainly don't think Don's hard line on cross-controlled stalls is unwarranted for him, nor am I inclined to say that pilots who report their Mooney "snapped hard over" are fibbing or confused about it. It's true that without aerobatic time or at least commercial steep turn training, anything greater than 45 degrees of roll can seem like knife edge when it's not, and that may be part of the story. But not all of it. I don't have any explanation for my experience being different than others, except to guess that slight mis-rigging or minor leading edge dents in a Mooney deliver a lot more devilish behavior than the equivalent mal-adjustment in a fat-wing airfoil.

-

Budgeting against TBO/Reserves?

Vance Harral replied to BlueSky247's topic in Miscellaneous Aviation Talk

People who point out an overhaul could be needed at any time are correct, but there's a separate aspect of this that may or may not matter to you: valuation. Even though you can't predict when an overhaul might be needed, everyone still appraises aircraft based on engine hours, and sales prices generally reflect that. For example, it would be reasonable to appraise M20J airplanes with a $20/hour engine time adjustment, based on an estimated $40K overhaul cost and 2000 hour TBO. A specimen with a fresh overhaul might be advertised at $140K; while an otherwise identical specimen with 2000 SMOH might be advertised at $100K. Now, the former could suffer infant mortality and need major engine work next week; while the latter might go another 1000 hours with no trouble. But because valuation is a statistical betting game, the difference in asking/sales price is going to be close to the cost of an overhaul, and therefore the value of an airplane really does decline significantly with engine use. So... if you have reason to preserve the value of your aviation enterprise, you might put $20/hour into an engine kitty, such that the value of the actual airplane plus the value of the kitty stays relatively constant (modulo market fluctuation, inflation, etc.) If you sell the airplane before overhaul, you likely get out about what you put in, from the sale price plus reclamation of the kitty. If you overhaul the engine before you sell the airplane, you'll have to come up with additional funds because the kitty won't cover it. But at that point you'll have an airplane that is worth more than when you bought it - probably about as much more as the out-of-pocket funds you used to cover the difference between the kitty and the actual overhaul cost. It's fair to say this is kind of a silly exercise for a private owner using an airplane for pleasure - I agree with @MikeOH that you can either afford it or you can't. But it can make a lot of sense to fund an engine overhaul kitty in a partnership, or in an airplane that is primarily a business asset. -

Stories like that remind me to be grateful that Denver TRACON is pretty accommodating of VFR traffic. They do steer you away from KDEN itself, but you can usually get clearance through the outer rings. I do get “remain clear” during pushes, and sometimes when I’m trying to coach a student pilot through the process and I can sorta tell they just don’t want to deal with them. But in general, Denver Approach treats us bugsmashers well. Sorry you don’t have the same luck in Atlanta, but at least they have the courtesy to tell you to remain clear. I’m told that Chicago TRACON just simply doesn’t answer calls from VFR traffic. Unsure if that’s just a rumor, I’ve never tried to gain entry there.

-

The usual "not realistic" complaint about ATC stuff is from people who say they're never going to fly anywhere "busy". No Class B or C, and only the sleepiest of towered airports. It is indeed true that you're unlikely to get that kind of stuff flying from, say, Platte Valley, CO to Sidney, NE; but I don't care. Still good to practice button-ology under stress anyway.

-

It mostly seems to boil down to experience, as experience tends to mitigate the adrenaline rush when presented with an even slightly abnormal situation. Pilots with lots of hours seem to do better, pilots with fewer hours get more flustered. My guess is that less experienced pilots are more overwhelmed with the idea of switching to "Plan B", particularly when it involves telling ATC (real or simulated) they need special accommodations to get re-situated. Note that "experience" doesn't necessarily mean piloting experience. There can be positive transfer from other jobs that involve managing complex systems: anesthesiologist, power plant operator, fireman, etc. Having said that, it certainly it helps to be a engineering nerd type (like me). Ideally the client has studied the the block diagram of their avionics installation - there's a good article advocating for this at https://www.ifr-magazine.com/avionics/avionics-systems-issues/. But even if they haven't, nerd types almost immediately "get it" when I say something like, "the magnetometer that senses heading information is in your wing, and there's a long communications wire that runs from it to your HSI. It snakes through a lot of twists and turns in the wing and fuselage, maybe it came unsecured and then got cut". Folks without this background just know there's a "computer" driving the TV screen in front of them, and tend to assume its a single, integrated thing; and that if one piece of information it displays starts acting up, that the whole thing might be unreliable. That's what I'm trying to accomplish. I fail things I think the client might be overly dependent on. If that causes a conflagration, we make a plan to learn not to rely so much on that particular device. Or, if they simply can't live without it, I point out they really need to buy a second iPad/install a second GTN650/etc. That would be the holy grail, but it's a very tall order in the modern era. As you point out, AATD panels are highly customizable, but also very expensive, so the local flight school that has an AATD typically has just a couple of panel variations, that only match (maybe) their own airplanes. Garmin is on the right track with their latest PC-based avionics simulator, which allows you to build and simulate a custom avionics cockpit model, see https://www8.garmin.com/support/download_details.jsp?id=12373. But that system only simulates Garmin products, of course, and only the later/higher end ones at that (no option for GNS navigators, no G5/GI-275). It's also not a flight simulator, just an avionics systems simulator. And it doesn't have any capacity for simulating failures. This challenge gets somewhat back into my rant in the other thread, about "new" avionics. There were multiple, competing suppliers of NAV/COMs fifty years ago, but there was effectively a universal standard interface to them: VHF frequencies and OBS bearings. Training in one airplane or simulator was highly transferable to another. That's no longer true today. People started talking about this in the G1000 era, but it's only gotten worse. Knowing your way around a G1000 is only slightly helpful if you sit down in front of a G500/G3X/GTN setup. You're in better shape to fly behind a G3X/G3XTouch if you've flown with G5s/GI-275s, but you should still plan on hours and hours of training (not necessarily involving actual flight in the airplane) to get up to speed. And all that Garmin experience is almost completely useless in an Avidyne or Dynon-equipped platform. You might not think this is a big deal at first, if you only fly one airplane. But when you get together with your buddies at the airport pancake breakfast - or here on Mooneyspace - you can't necessarily help each other out with question about panels and procedures because you don't have the same stuff. Worst of all, even when you think you have the same stuff, a true nerd like me will come along and point out that you're not both running the same firmware version in your gizmo, and therefore will see slightly different behavior than your buddy. If I were pie-in-the-sky daydreaming, I might put together an open source project, and try to convince all the avionics manufacturers to interface their training simulators into that project, which in turn would interface to Xplane and/or Pepar3D and/or Redbird. It sure would be nice. But that's a tough enough engineering challenge, and that's the easy part. Convincing the manufacturers to participate would require an exceptionally skilled businessman/politician.

-

Lightspeed headset special offer

Vance Harral replied to NotarPilot's topic in Miscellaneous Aviation Talk

Sounds like @CVOhas already tried the simple stuff. But for what it's worth, I've found anecdotally that "popping" in an ANR headset is sometimes caused by simple things that break the integrity of the ear cup seal. e.g. vibration on ground roll or in turbulence that makes the headset move around on your head; turning your head; wearing glasses; and in some cases just one's head/ear anatomy not being a good match for the seals. I rarely get this popping in my Gen 1 Lightspeed Zulus, but when I do, the first thing I try is just using my hands to press the ear cups a little more tightly to my head. If the popping goes away, then I start thinking about whether the size adjustment mechanism slipped, the ear seals popped off their mounts, I'm wearing thick-earpiece spectacles, or whatever. It's my understanding there is an implicit assumption in noise cancelling control loops, that the in-the-ear-cup environment is mostly isolated from the outside environment. If that assumption is violated, the control system temporarily overdrives the speaker that is supposed to be producing "anti noise". That can definitely cause popping. To be clear, not suggesting anyone should have to fly around with their hands on their noggin, clamping their headset even more tightly to their head. Just saying it's a simple thing to try first. -

In the realm of "advanced avionics", I practice a couple of philosophies with instrument students/clients. It's not a list of specific tasks, but rather a set of concepts that go like this: 1) If a client demonstrates any reasonable degree of basic instrument proficiency, then I'm allowed to fail anything I want, at any time, provided I can do so safely and legally in simulated conditions. I make no argument that said failures are "realistic", because that's not really the point. What I'm trying to do is build systems knowledge (in some cases my own as well as the client's!); and to build general strength and confidence when things stop operating as expected. For example, I'm aware that a simultaneous power-down of two G5s/GI-275s at the same time is unlikely, but I don't care - I'll fail 'em simultaneously anyway to see how the client responds. Do they make good use of the AV-20 they installed "just in case"? Do they use Foreflight to display attitude from a Stratux/Stratus/Sentry on their iPad? Do they revert to needle/ball/airspeed? Any of those are reasonable. What I don't want to see is them saying they'd troubleshoot why the G5s are dead while hand-flying in IMC, and/or complaining that "this would never happen in real life". Similarly, I'll pull a GAD29 breaker such that the navigator can't talk to the ADI/HSI, even though it's very unlikely that device would fail by itself. I want to see if the client recognizes they don't have lateral/vertical indicators (or if they actually still do, it turns out this depends on how the devices are wired and whether it's a GPS vs. ground-based approach), and what they do about it. And of course I fail individual ADIs/HSIs, autopilots, and the primary GNS/GTN/IFD navigator. 2) I'm allowed to ask for any kind of navigation procedures I want, regardless of how likely it is one would have to use them in real life; particularly if I've failed other nav equipment per (1) above. VOR approach? Yes. VOR/DME if you have DME installed? Yep. ADF approach? If you've got a working one and we can find an approach, then yes. Steering the ownship icon back and forth across the course line on a geo-referenced approach plate in Foreflight? Absolutely I'll do this, if the client has said or even hinted they'd do so in an emergency. The point of this is not to convince the client to maintain proficiency with "old" or "alternative" equipment. It's to put them in an uncomfortable situation, and in a lot cases, force them to realize that their backup nav solution isn't actually viable, because they don't really know how to use it. This sometimes leads to a post-flight learning along the lines of, "If my XXX gizmo fails, I will declare an emergency and seek VMC conditions"; rather than "I will attempt to use my backup nav solution to fly an approach". 3) I'm allowed to throw any simulated ATC curveball I want during instrument procedures, regardless of how realistic it is. Unexpected hold? Yep. Last minute change in which approach to fly? Yep. Slam dunk approach from above the glideslope? I'm your huckleberry. Request to "keep your speed up"? I'll do so with my best faux east coast accent. If you request vectors to final, I'll tell you to expect it, then clear you to an IAF or IF instead. If you load the full procedure from an IAF, I'll be sure to vector you onto final instead. You're probably getting the theme here. I don't particularly care how "realistic" any of this is, I'm just trying to force the client to work harder, faster, and - in most cases - realize the stress level of doing so is dramatically influenced by how good they are with button-ology. It's a powerful motivator to get them to work with a nav trainer on the ground to get better. That's my take on it, but I'm likely one of the lesser experienced CFIIs here on the forum. Looking forward to what others have to say.

-

Advance apologies... I'm triggered. As a denizen of an airport where last call has come in vogue, let me opine... it's dumb. This idea that you are "letting people know you won't be calling or listening to the frequency any more" is dumb. What are the other aircraft who are still on frequency actually supposed to do with that information? The biggest irony around here is that it's sometimes not even the last call made on frequency by the aircraft in question - the pilot kiddos using it change their mind, and make another call, often accompanied by a second last call. To date, I've managed to avoid keying up and asking if it's their real last call, or their next-to-last call... but I say it in my head, and sometimes to my students. It's not so much the call itself I mind, as the lack of awareness about its use. I lump it in with other, useless "callouts". Let's be honest - a lot of this stuff gets said because it sounds cool, and makes you feel like a big boy pilot. Perhaps it seems "standard", and maybe - if you haven't actually thought it through - it seems "safe"... but the safety purpose of CTAF calls is to provide immediate, actionable information to other aircraft on frequency. I'm increasingly frustrated that pilots around my neck of the woods - those from the nearby flight school airport in particular - are instead using it as a way to verbalize a checklist for everything they're going to do in the next five minutes; and throwing in Walter Mitty style points at every opportunity. For example: KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is on frequency, five north at 6500 feet. We'll teardrop over Runway 29 and enter the pattern on the 45 for a short approach to a touch-and-go, then departing south back to KYYY . KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is overhead at 6500 feet, teardropping over Runway 29 to enter the pattern on the 45 for a short approach to a touch-and-go, then departing south back to KYYY . KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is on the 45 for Runway 29, doing a short approach to a touch-and-go, then departing south back to KYYY. N54321, we see you on crosswind. Do you have us in sight? (N54321 responds, a conversation is had, often with an "ADS-B position checks!" thrown in for good measure.) KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is on (downwind/base/final) for Runway 29, number two behind N54321, for a touch-and-go, then departing south back to KYYY. KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is actually going to make this a full stop. We'll exit at Alpha 4 and taxi back on Alpha. KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is clear of Runway 29 at Alpha 4 short of Alpha, we'll be taxiing Alpha 4 back to Runway 29. KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is taking the active, Runway 29, for a straight out departure, followed by a south turn back to KYYY. KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is climbing out on the departure leg from Runway 29 at 5600 feet, we'll be turning south and departing back to KYYY. KXXX traffic, bugsmasher N1234 is departing the area to the south, back to KYYY, LAAAST CALLLLLL.... SEEYA! I wish I was exaggerating about this, but I'm not. Any single one of those calls might be forgivable by itself. And I wouldn't particularly care about it if we were some sleepy airport in the middle of nowhere. But as other airports have increasingly shunned pattern work, ours has become the go-to-spot in the metro area for touch-and-gos, and it's not unusual to get half a dozen airplanes in the pattern at the same time. That'd be fine if people could have a holistic view of why we communicate on CTAF. But there always seem to be a couple of training mill pilots in the mix; making their "standard callouts" as above; obliviously stepping on an aircraft trying to broadcast their turn to final, in order to get in their "taxiing back" standard callout; and sprinkling in 30-second, two-way conversations with whoever is closest to them, in the supposed name of traffic avoidance. All this ignores the fact that they're taking away the frequency from everyone else in the pattern. Again, the real purpose of the CTAF is to provide immediate, actionable information to other aircraft on frequency. Where you are right now, maybe what you're doing in the next 10 seconds, and that's it. That doesn't mean the rules are rigid, that you can't ask a question, or say "Hi, Bob" on a quiet day. But before you key up that mic, you should ask yourself how busy it is, and if it's busy, how the thing you're about to say is actually helpful to anyone other than yourself. In that environment, last call doesn't pass the smell test. And if it's not appropriate at a busy airport where there's a bunch of other traffic, why would it be appropriate anywhere else?

-

This guy is an embarrassment to Mooney pilots.

Vance Harral replied to Brandt's topic in Mooney Safety & Accident Discussion

Yes on the last two, no on the first two. Modern equipment requires more skill and more education to be proficient than older equipment, and that's a new challenge that has everything to do with the equipment, and almost nothing to do with the person. Many folks understand this, and plan for the additional training and practice required to reap the benefit. But many do not, and are surprised to find out (or be told) they are actually worse off with new tech than without it, despite having entirely reasonable attitudes about training and proficiency. Not all of them respond to that cognitive dissonance the way we wish they would. I suspect we're not very far apart in our opinions about modern avionics. With sufficient practice and training, they can definitely enhance safety for a particular pilot. But there simply isn't any evidence they're making flying safer for the GA population as a whole. Anecdotally, I don't see it when I give flight instruction to dozens of clients. Statistically, it's just not there in the accident/violation data. When I rant about this stuff, I'm really trying to figure out how we change that. All I know for sure is that just having the gizmos in the panel isn't enough by itself, even though most of my clients have pretty good attitudes. Something is missing. -

This guy is an embarrassment to Mooney pilots.

Vance Harral replied to Brandt's topic in Mooney Safety & Accident Discussion

If you're referring to my posts, I'm not arguing that modern technology is making pilots worse, only that it's not moving the needle one way or the other when you look at the data. The VFR-into-IMC accident rate isn't moving. Neither is the midair collision rate. I appreciate that @Marc_B took the time to type out a lot of details about the information and capability modern equipment provides. But he doesn't give evidence that the accident rate is getting better, he only gives theories about how those technologies could theoretically prevent accidents. It's a sales job, not evidence. To cherry-pick a few things from his post: ... then why didn't the pilot who is the subject of this thread just do that? Instead, he said, "I'm having trouble controlling the plane and doing stuff at the same time", and that his "main GPS" (assuming it was the panel mount unit) "was totally wrong" I know it's de rigueur to just say he was an idiot, but the reality seems to be that it's not as easy as you posit, across the pilot population as a whole. That statement doesn't apply to Marc as an individual, of course, but he's just one data point. ... provided you (1) haven't accidentally (or deliberately) turned them off with a declutter operation; and (2) fully understand how the technology that transmits the data can fail to complete transmissions. Mooneyspace pilots are surely a cut above average, and absolutely no one here is more qualified on their cockpit technology than @PT20J, so why was this an issue: https://mooneyspace.com/topic/43573-missing-ads-b-tfrs/ Whatever the case, pilots are still flying into TFRs on a regular basis, even as the fleet is better and better equipped to depict where they are and warn you when you're approaching them. The incursion rate today isn't any better than it was 20 years ago. It's great technology, but the question is why some pilots are unable to use that button, in the "heat of battle", so to speak. I incorporate the LVL button into flight training, in aircraft so-equipped. In the last couple of flight reviews I gave in thusly-equipped airplanes, the pilots couldn't really tell me when/how they expected to use the button, just that it was there "in case they needed it". So I put them in unusual attitudes, and they performed the FAA-standard recovery by hand (poorly). When I asked them, "Why didn't you just press the LVL button on the autopilot?", they basically said it didn't occur to them. If you think they'd behave more rationally in the fear and stress of an actual disorientation event, you're dreaming. To beat a dead horse... Equipment is just equipment. It's not safety by itself. To convince me that a technology actually improves safety, or reduces legal violations, or whatever... you have to show data. Yes, the accident data is sometimes difficult to find and/or interpret. But between not seeing any meaningful change in the accidents and violations covered in my Flight Instructor Refresher Courses, and my actual experience teaching as a flight instructor, I'm confident the last 20 years of technology isn't delivering on the promises its advocates make for it. That doesn't make the technology itself bad. It may indeed deliver on promises in the future, as education and training behavior changes. But we're not there yet. And it's specifically true that lots of pilots dumping AMUs on "safety" in their avionics upgrades are actually achieving nothing of the sort. Perhaps, like we say, "Pitch plus power equals performance", we should all start saying, "Equipment plus training equals safety". As I mentioned above, the irony of this is that you need more hours of training to actually improve your odds with modern technology. Finally, a punch line... the last person I gave the LVL test to quit flying with me after that flight, which also included an instrument approach that he never actually loaded into the navigator. I firmly but politely told him not to use the privileges of his instrument rating until he got additional training. He didn't like that, and also insinuated he didn't think I was worth the $65/hour I was charging him, to train with the $50K panel he'd just put in his PA-28. A few days later, he departed Colorado after dark, and flew through the night all the way to Arizona, over pitch black mountainous terrain, undoubtedly confident in the safety of his high-end panel. It turned out OK for him - that time - but my signature is in his logbook a couple of times, and I can't take it back. Maybe that story helps all of you understand why I'm so wound up about this stuff. -

This guy is an embarrassment to Mooney pilots.

Vance Harral replied to Brandt's topic in Mooney Safety & Accident Discussion

Well, then, what's the point of it? Yes, statistics are complicated, and I also understand the theory of risk homeostasis. I'm not a Luddite, and I've enjoyed every technology advance in aviation during my flying avocation/career, largely because they sit at the intersection of my airplane addiction and my nerdy electronics bent. I just haven't seen compelling evidence that we're particularly safer for it. Maybe we are indeed more capable. It's possible a lot more IFR missions are being completed in single engine pistons that used to be, and that's a good enough reason to like the new hotness. This is the crux of my point. There are some pilots who I'd trust in IMC equipped with nothing more than vacuum gyros and two NAV/COMs, because they frequently practice for the relatively straightforward failure modes of that equipment. There are others I wouldn't trust with two WAAS GPSes and four sources of attitude information (not an uncommon configuration these days), because they've never trained for anything other than nominal, simple scenarios. The irony is that folks in the latter category aren't necessarily training fewer hours than the former, there's just so much more to cover. Occasionally the latter group will deride the former for being "too cheap for aviation", though that's kind of a bogeyman argument that's actually pretty rare. What I find more common is clients who are very excited about the safety aspects of their recent $25/50/75K panel upgrade, but who demonstrate to me in a flight review that they don't know how to use it in anything other than a small number of scenarios. That's not a recipe for safety, but a lot of them truly believe they've "put their money where their mouth is", with respect to being safe. -

This guy is an embarrassment to Mooney pilots.

Vance Harral replied to Brandt's topic in Mooney Safety & Accident Discussion

OK, I'll play. Give us your argument. Many people want to believe your assertion is true, and tell themselves so as they shell out tons of dollars on "capability" (but disturbingly little on "training"). But overall GA IMC accident data just doesn't show a meaningful decline, despite the fact that on average the GA fleet grows more sophisticated every year. Here's one article with data: https://www.aopa.org/training-and-safety/air-safety-institute/accident-analysis/vfr-into-imc/ntsb. Yes, I know that if you draw a linear average, those graphs show a slight reduction in the accident rates over time. But viewed holistically, the rate is just bouncing around, same as it has done for decades. Indeed, two of the absolute worst years in the last couple of decades were 2017 and 2019, long after the introduction of the latest round of navigators and autopilots, and just before the Covid-induced proficiency lapses. So there just isn't any evidence of a great revolution in safety as all these gizmos get put in panels. Bottom line: equippage is just equippage. It's not capability or safety by itself. As others have noted, the more capability we have, the more practice and training is required to truly benefit from that capability, and most of us just don't get all the bases covered. I'm not so arrogant as to think I'm special in this respect. Proficiency with buttonology in the multitude of airplanes I'm asked to give instruction in is one of my biggest concerns. Presently, I'm expected to be proficient with all of GNS, GTN (Xi and non-Xi), and Avidyne navigators; vacuum gyros, G5s, GI-275s, G500 Txi, and G3x Touch. I won't actually take an Avidyne or GI-275 equipped airplane into IMC, but that's not because those aren't highly capable devices, it's just because I just don't get enough time with them to be instrument proficient. If someone asks me for instrument instruction in a Dynon-equipped airplane, ethics will demand I decline. Which is a bummer, because those are cool toys. But as Harry Callahan said, a man's got to know his limitations. -

Instrument Approach Gear and Flap Sequence - A survey

Vance Harral replied to midlifeflyer's topic in General Mooney Talk

Excellent point from Don, and this can be done in any Mooney, including those without speed brakes. It can be done in any airplane at all, provided you understand the time and distance it takes. I always cringe a little when people say things like, "You can go down or slow down in a Mooney, but not both!". That's bunk. Pitch plus power always equals performance, it just takes longer to stabilize at a particular point in a less draggy airframe. That said, it's certainly reasonable for any particular pilot to say the challenge/risk of of a constant slope variable airspeed approach isn't worth the benefit, especially if it takes a few miles to reach the new set point. Mostly it's a matter of how much you've practiced it. We all have limited time and dollars to practice, and simple isn't bad. -

Aside from using slightly taller/longer tugs and tow bars without hitting the prop in the vertical position, I can't think of much. It certainly doesn't make any operational difference in what runway surface you could/would accept. I think the, "Be careful, a Mooney doesn't have much prop clearance" thing is overblown. A PA-28-161 has an advertised minimum prop clearance of 8.25", and an A36 is 7.25". An SR-22 clocks in at 7" even. And those airplanes are a lot more likely to reach their minimum clearance than a Mooney, due to them having a conventional oil/air nose strut vs. the Mooney's shock disk design. All these airplanes are more likely to drag their prop through the dirt pulling off the runway into the grass at KOSH than a Cessna 170, of course, but it's not like the Mooney is particularly special.