-

Posts

1,416 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

3

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Gallery

Downloads

Media Demo

Events

Everything posted by Vance Harral

-

It only has to do with where the fuse/CB breaker is placed, through the mechanical size of those different devices may dictate where they wind up. Otherwise, there is no truth to this idea that one type of circuit interruption device is designed to protect wiring and another to protect the appliance the wire connects to. That's just not correct. Both types of interruption devices can protect both wiring and appliances. Both types of interruption devices provide more safety when placed on/near the bus bar than on/near the appliance being powered. This is due to the nasty failure mode of a power wire which chafes and shorts to ground between the bus bar and the appliance, and winds up carrying more current than it's rated for. This type of failure tends to melt the insulation, dribbling hot, waxy gobs of plastic-like material onto surfaces like clothing and carpet that are prone to catch fire. It's nice to protect the appliance too, but the failure mode of an internal short in the appliance tends to simply burn out a component that's encased in a metal box. It could still hurt you or start a fire, but that's much less likely than an over-current wire. If you can only place one circuit interruption device in the electrical path to an appliance, putting it near the large, robust (cool) bus bar is good because it means most of the wire that might melt is "downstream" of the circuit interruption device. If you instead put the interruption device near the appliance, most of the wire that might short is "upstream" of the interruptor. That's true regardless of whether the poorly-placed interruption device is a breaker or a fuse.

-

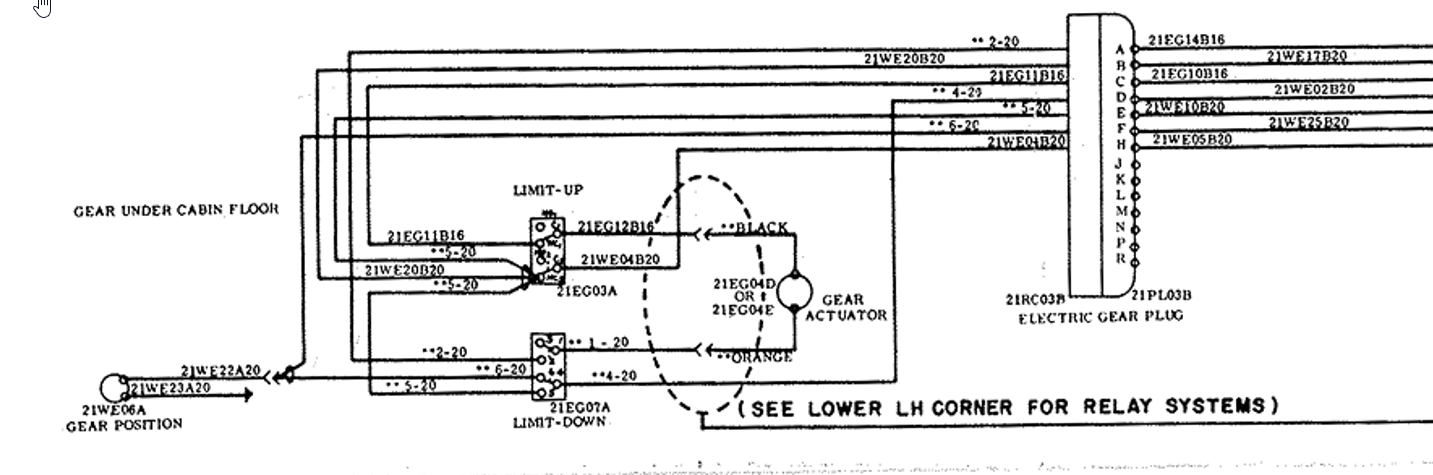

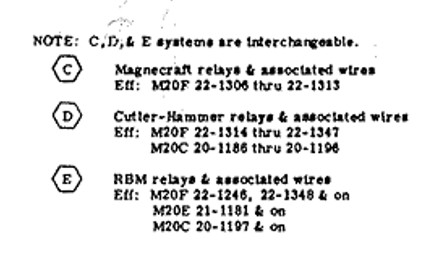

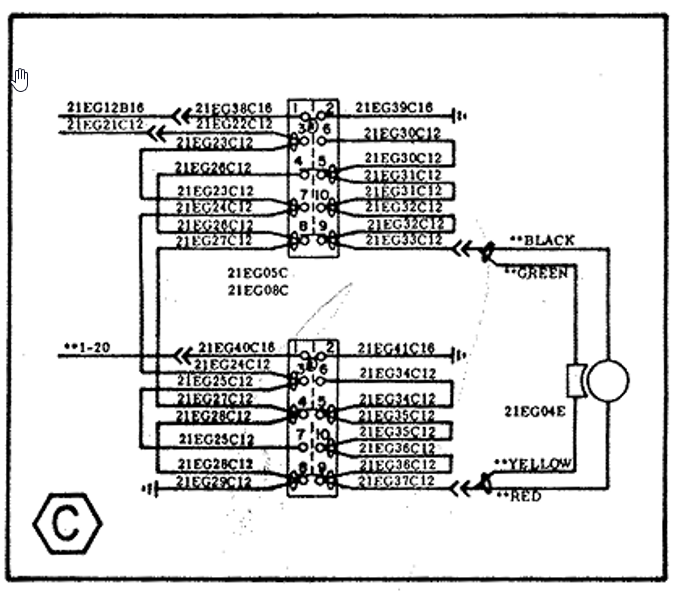

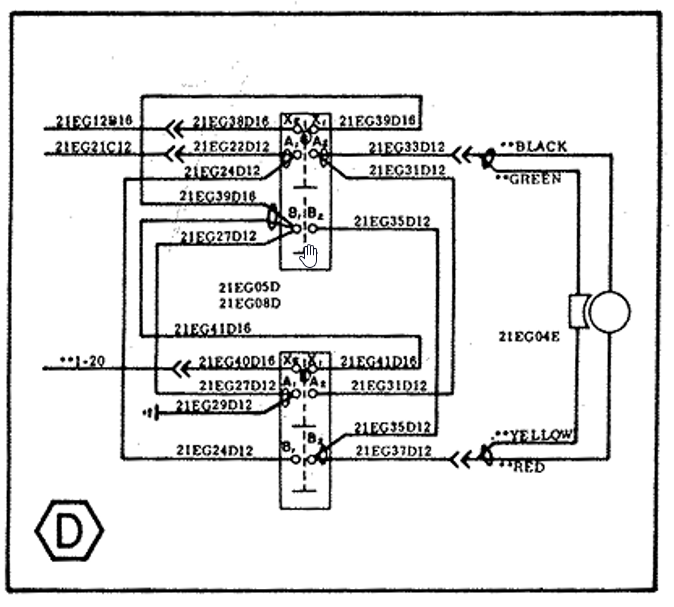

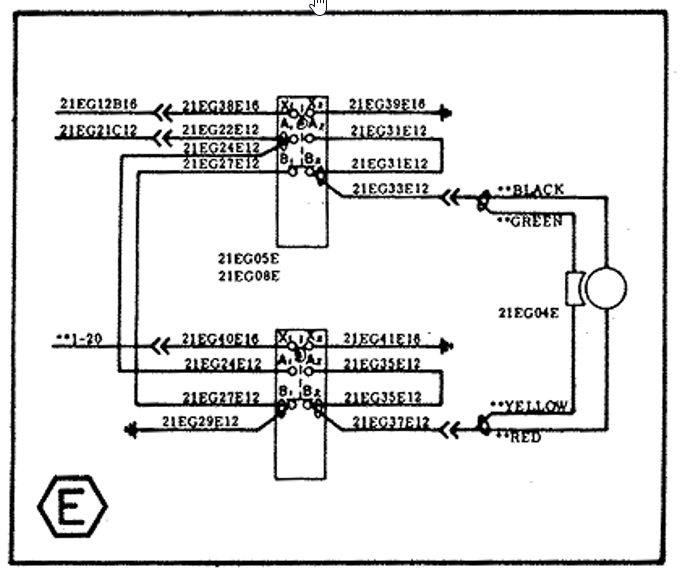

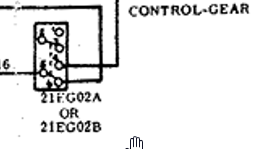

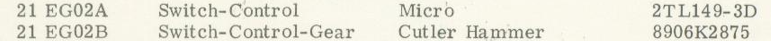

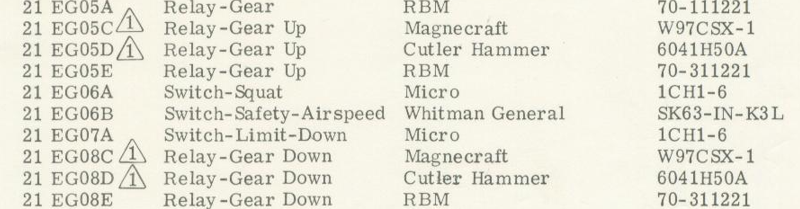

Screen captures of relevant details for M20F s/n 22-1306 and on are pasted below, from a high-res schematic Mooney sent us a long time ago, and the service manual. Part numbers are OEM original from the 1970s. My guess is that some/all of them have been superseded, but you can look up equivalents online. Not sure what you mean by the "switch to drop the gear", as there are a number of switches in the system: the pilot control switch in the cockpit that selects gear up/down, the relays that power the landing gear actuator motor, and the limit switches that cut power to the motor when the gear reaches its final up/down position.

-

Peace and Godspeed, sir. Thanks for being part of our community.

-

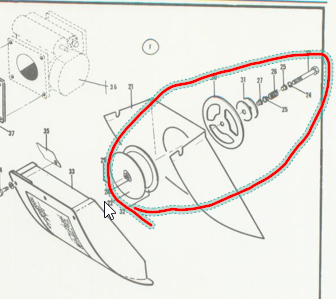

The alternate air mechanism in the E/F is completely independent of the ram air port, and I suspect it's the same in the J. I've circled it in red in the figure below, clipped from the parts manual picture above. It's a round door at the back of the air box, which is ordinarily held closed by spring pressure. If the air pressure inside the air box gets sufficiently lower than the air pressure outside the air box (presumably because the normal intake path through the air filter is blocked), the air pressure difference overcomes the spring pressure and opens the door, drawing air from inside the engine cowl. The mechanism is completely automatic, there is no control in the cockpit for it. The mechanism should be periodically checked (annual, oil changes) for freedom of movement against the spring. Note that if you're in conditions which you suspect might clog the intake system (ice, volcanic ash, whatever), it is critically important to keep the ram air door closed. Opening the ram air door directly exposes the impact tubes of the fuel servo to an unfiltered air stream. If ice or dirt or whatever in that air stream clogs those tubes, the fuel servo stops working as designed, and it's pretty much game over. You can't fix it by closing the ram air door, and the alternate air door won't do you any good. I'd argue that the ram air port is actually the antithesis of "alternate air", since its use is more likely to cause an intake emergency than it is to bail you out of one.

-

It seems to me that the geometry of the components prevents this. If you look at that parts manual diagram above, the lower images are for the carbureted engine. The carburetor airbox is directly inline with the intake path through the air filter. Any mechanism that bypasses the filter would have to take a roundabout route to get to the airbox. I don't think there is room in the cowl for such a mechanism, but even if there was, it would create the same kind of circuitous route the E/F have through the normal intake path, and thereby reduce the benefit of the ram air.

-

The system is substantially different on the E and F models vs. the J, due to the different cowl. A page from the parts manual and a picture of an M20F are attached below. It's a little hard to follow the parts manual picture, so start with the picture of the actual airplane. In that photo, the ram air port is the rectangular hole directly below the spinner and directly above the air filter. The important thing to understand in the E/F models is that the fuel servo air intake is directly behind the ram air port, but somewhat above the air filter and the air box behind the filter. Therefore, when air enters via the normal intake path, it passes through the air filter, then it must travel an S-shaped path through the air box to get to the fuel servo. If the ram air door is opened, then not only is the air filter bypassed, but the incoming air also has a direct path to the induction system. This is why ram air is somewhat effective in these models. In the J model, the normal induction path is more efficient, hence less benefit from ram air.

-

M20F takeoff and landing performance charts

Vance Harral replied to cstoffel22's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

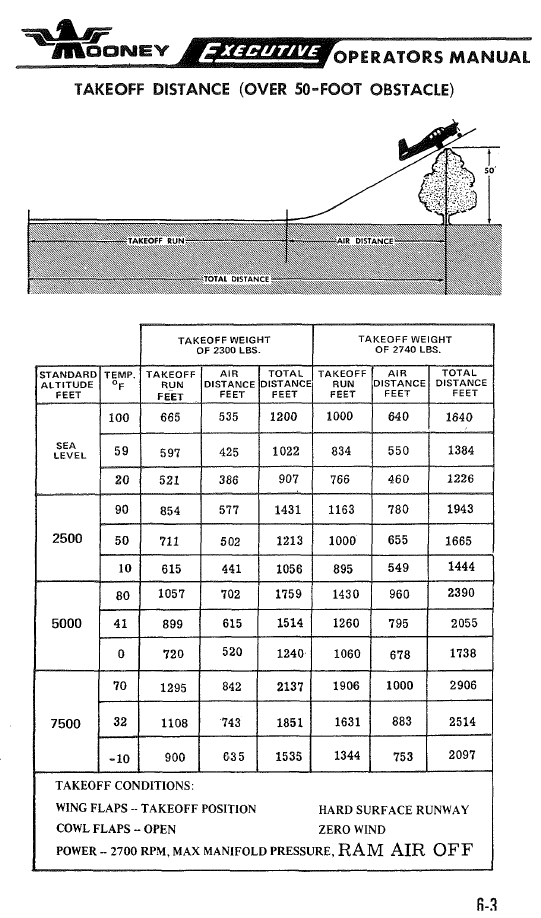

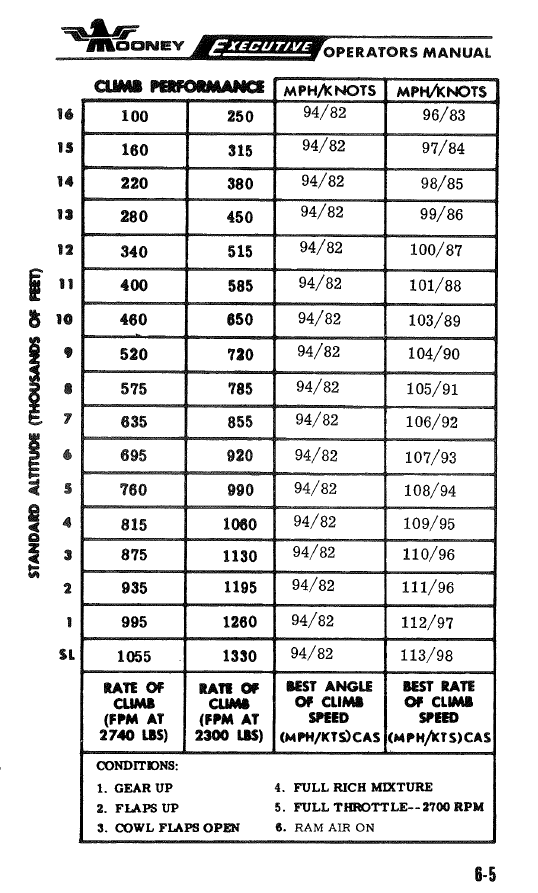

F model takeoff and climb data from the Operator's Manual is pasted below. Note that the takeoff data includes a data point for 7500' at 70 degrees F, which is 10,000' density altitude. Landing distance is shorter than takeoff distance in all cases. We've operated an F model out of the Denver area for 20+ years with no complaints. I've flown it to Leadville, etc. People who say you'll never go back once you've flown a turbo are generally right, but a lot of dual instruction given in K models hasn't made me dislike our F. However, we don't do much hardcore traveling due west over the rocks. -

Those diagonal braces are factory parts installed on early-year-model M20B/C/D/E/Fs, but not later year models. You can see this in the progression of the parts manuals. Parts manual 202 for the 1961-1964 M20B/C/D/E shows the braces for the B/C/D on p. 106 and for the E on p. 111; and there are no applicability notes, i.e. all airplanes in those year groups have them. Parts manual 203 for the 1965-1967 C/D/E/F shows the braces for the 1965 models on p. 165 and the 1966-67 models on p. 170; but there are per-serial-number applicability notes, which indicate not all airplanes had them. Parts manual 205 for the 1968-1976 models do not show the braces in any diagram and make no mention of them in the parts list. It seems clear that at some point the factory decided the braces were unnecessary and/or caused more problems than they solved, but I do not know why. Our 1976 M20F does not have the braces, but the cowl still has the attach points for them. So every once in a while, some mechanic understandably tries to tell us ours are "missing", and I have to dig out the parts manuals and show them how the factory stopped installing them some time in the 1966-67 time frame. My guess is that Powerflow lists the braces as separate options because they are only supposed to be installed on the earliest year models. If you don't have them, I'm guessing you have a later year model airplane. If you feel they'd be beneficial to you and you want to be "legit", there is probably some legal way to install them using the earlier year models as the basis for approval. But I'll leave that to the actual A&Ps to comment on.

-

Our M20F has ram air, and it's benefit is higher than the M20J due the less optimal induction path with the older cowl. If I'm paying close attention, I can see just under 1" of MP increase by opening the ram air door at varying altitudes. However, the resultant change in cruise speed and/or climb rate is negligible - basically too small to see. The "benefit" is so uninteresting that everyone in the partnership quit fiddling with the ram air control a long time ago. All it seems to do is present an opportunity to forget to close it toward the end of the flight, and thereby ingest unfiltered air into the engine during descent. It also causes us occasional maintenance grief when the rubber seal on the door dries out, or the cable needs to be lubricated, or the warning annunciator circuit gets out of whack. We maintain the system because we want everything on the airplane to work as designed, but if someone offered free parts and labor, we wouldn't hesitate to have it deleted. The benefit with the M20J cowl is even less than on older models, which is why the factory deleted the feature in later years.

-

I'll try to get a data point on this when we have our tanks resealed in February, but it'll just be one data point. We're a good poster child, though, because the fueling policy in our partnership is to fill to the tabs (not full) after each flight, and it's been that way for 20 years. That means we have two decades worth of having the bottom portion of the tank full of fuel almost all the time, and the top inch or two almost always dry. We have several seeps on the bottom of the wings, and I know both tops seep a bit (right worse than left) if you fill the tanks and let the airplane sit an hour or more. Our airplane is hangared, so we don't have the effect of sun heating the top half of the wings with air in the top half of the tanks. But if being immersed in fuel vs. not really makes a difference, I can't think of a much better candidate for a data point than our airplane. If there's a difference and it's visible, we ought to be able to see it.

-

Much as I like our Mooney, this is the sort of thing that really shows how the airframe is sliding into obsolescence. I understand people are just trying to keep their birds viable without breaking the bank, but I cannot imagine jacking up my airplane and/or installing locks in the landing gear suspension to "save the landing gear doughnuts". The risk of the airplane falling off jacks is pretty small if you're careful, but it's a catastrophic event if it happens, and the likelihood of it happening goes way up if you're doing it literally every time you put the airplane away. Lots of airframe models remain viable after being orphaned by the manufacturer (and let's not kid ourselves, that's the state of Mooney). But beyond a certain point, it becomes ridiculous. Imagine the reaction of a potential new owner, or the peals of laughter from the local hangar crowd. "Yeah, a Mooney is a pretty nice airplane, but the design of the landing gear is so dumb that you've gotta put it up on jacks when you're not flying it".

-

That's probably the correct range for airplanes with larger tanks: later models from the factory and/or those with Monroy long-range STC. Yep, that was our strategy for two decades, and I don't regret it. The cost of the patches worked out to less than $5/hour for us, which is arguably in the noise of operating cost. But nothing lasts forever. You have to guess at how much longer you think you'll own the airplane, estimate inflation, time value of money, etc. I kinda wish we'd ponied up for that "too expensive" paint job in 2005, when we could have had a pretty good one for under $10K. That same paint job would be over $20K now. As for the G100UL thing, I guess it remains to be seen the degree to which this is actually a function of tank sealant health. We're of course hoping a fresh seal job buys us some insulation against the problem, if we use G100UL in the future. But there isn't enough at-scale-in-the-market data to be sure, and for better or worse we're not going to wait on it. If G100UL is a major cosmetic problem for people like us who ride the tail of the sealant curve, I can only imagine how irritated people with young sealant (and often nice paint jobs) will be if G100UL turns out to be - even just cosmetically - incompatible with wet wings.

-

No criticism of your strategy, we also paid $1-2K for patches every few years, for the last 20 years, and it served us well. That said, your estimate for a reseal is pessimistic by more than $5K. After about 50 years of original sealant plus patches, we decided to bite the bullet, and have an appointment with Don Maxwell at the beginning of February for a full strip and reseal on our M20F with 64 gallon tanks (roughly the same vintage as yours, I recall). The contracted price is $9600 for both sides. 7 year warranty, for what that's worth. The $9600 quote doesn't include travel costs. Round trip from Denver to Longview in the Mooney will put about 8 hours on the airplane, but it's hard to say whether that should be included in the accounting or not, as we like to fly and would likely have gone somewhere else instead. Short-notice round trip airfare from Longview home, then back for pickup, adds about $750 (anyone traveling from northeast Texas to Denver around the end of January, and/or in the other direction around end of February?) I don't know whether to feel better or worse that we scheduled this reseal right before the recent news about G100UL and Mooney tanks. No G100UL in Colorado for now, but it's obviously a strategic concern. We're unconvinced bladders are a better bet on that front, and slightly prefer wet wings for other reasons as well. The other alternative was to do nothing, but we had reached a point where we were concerned the airplane might spring a significant leak that would make it difficult to deliver it even to a shop that would patch it. You also just get tired of looking at the ugly blue/brown stains after a while. Even when it's not a safety of flight issue, it starts to feel like you're neglecting the airplane and creating a major sticking point for sale somewhere down the road.

-

Couple of caveats about this. First, while the Duke's and ITT actuators are largely the same, one difference with the later ITT actuators is that they lack a Zerk fitting to add grease in situ. Thus, you can't "give it a few pumps of grease till it comes out the screw hole, while in the plane", at least not the way those with the Duke's actuators can. You can remove two of the screws and pump grease into one hole with a cone tip until it comes out the other. But I've never had much luck with this, as access is awkward and it's difficult to get the cont tip to actually seal well enough against screw hole #1 to pump through to screw hole #2. I've gotten to the point where I simply don't try to lube the gear cavity without removing the actuator from the airplane and disassembling it. I've done this enough times now that it's not a particularly big hassle. The other caveat is that if you use this technique of pushing grease through one hole (zerk or screw) until it comes out another, you've got to be sure to take enough grease out of the last hole before you reinstall the bolt, to ensure the bolt doesn't hydro-lock against the grease in the cavity, and strip the threads of the actuator. You can guess how I know this.

-

Fly with tie-down/Jack points removed?

Vance Harral replied to Jason 1996 MSE's topic in General Mooney Talk

In our stock M20F, the threaded hole does not extend into the tanks. This does indeed seem to be specific to the Monroy tanks. -

"Nice time machine you've built there. You going to go back in time and invest in Apple? Nvidia?" "Nah. Mooney landing gear doughnuts".

-

Of course not, but the question is how much "gas in the tank" the pilot has left, cognitively, to perform tasks above and beyond what's required for the IPC. As you note, lots of pilots wind up getting an IPC signed off not because they need one, but essentially by coincidence. Such pilots are active, proficient, and able to accomplish all the tasks required for an IPC without being mentally taxed, and therefore can meaningfully accomplish more than the required items in a single flight (I wouldn't call the IPC task list just "basic minimum items", there is quite a lot there). And in almost all cases, such pilots don't actually "need" the IPC because they're already instrument current, and very likely to remain instrument current for the forseeable future just by conducting training and/or real-life operations that gets them the 6 approaches, holding, and intercept/track. For pilots like these, the concept of "getting an IPC" is really just shorthand for wanting a high level of proficiency training. Whether there is an IPC signoff in their logbook is academic. As you might guess, only a subset of the pilots who come to me for an IPC fall in this category. The others are rusty, trying to regain currency, and I'm just trying to do my best to give them the best odds at making use of their rating (and frankly, keeping them alive). If I press too hard on the idea that an IPC includes more than the bare minimum, most of these clients are entirely game for it, because they understand that the end result makes them a better pilot. You would think that's a good thing. But that's just theory. In practice, the result is sometimes that the "IPC plus" flight goes somewhat poorly, I never see them again, and I'm left to wonder if the net result was actually an overall decrease in safety.

-

It's helpful not to confuse an instrument proficiency check with instrument proficiency training. As @bigmo notes above, meeting the requirements of 61.57(d) for an IPC is specifically and legally tied to a list of tasks in the Instrument Rating ACS, and all of them must be covered. The instructor (and their client) get to choose how those tasks are covered, and you can of course add extra stuff. But there's something of a cultural expectation that a proficient IFR pilot can accomplish an IPC in one session. If you start getting too creative in that one session, you wind up with a fatigued pilot at the very far realistic corner of the unusual situation/emergency envelope. That's not necessary helpful to anyone, and it doesn't meet the spirit of law that requires the IPC in the first place. So I don't try to "pack" an IPC with much more than the ACS task list itself. When I conduct IPCs these days, really the only item of much discussion is how to conduct an "Approach with Loss of Primary Flight Instrument Indicators" in an airplane with redundant EFIS displays. This is increasingly the default situation, because even the most pedestrian IFR airplanes tend to have at least a dual G5 or similar. I have a couple of comments about that. First, I'm not opposed to pulling a circuit breaker. I'm aware of the guidance from Garmin not to do so, but you've got to understand what's behind that guidance, which is more about confusion of pilots, instructors, and maintenance personnel than it is about any damage to the expensive gizmos. I've written about this in other threads, so I won't go into it here except to say that an electrically powered device can certainly lose power, and pulling a breaker is a way to simulate that. Like all abnormal situations, it's best to experience this on occasion in training, so you can see how small things can be quite disruptive. e.g. most dual EFIS setups will revert the primary attitude display to the backup display if the primary display loses power. This is great, but I've found that pilots tend to underestimate just how distracting it is to have their primary attitude information in even a slightly different location, even though it's the same display. In the case of the smaller EFIS instruments like the G5/GI-275, they may also not realize how hard it is to do without an HSI, even though the primary ADI shows course guidance information (in a different manner) at the bottom. But all of those things are less distracting on the first attempt than abandoning everything in the panel in favor of Foreflight on an iPad. To be clear, Foreflight on an iPad is a reasonable backup plan, but you've got to practice with it. Anyway... having said that, I also like the technique of simply using backlight controls to dim an ADI display down to the point of it being invisible (working perfectly fine, you just can't see it). There are a couple of reasons I like this approach. One is that while we tend to be enamored of the "redundancy" of dual G5s or whatever, that redundancy only kicks in when a device loses its bus link to the other device - typically due to a complete loss of power. That is not the only - or I suspect even the most common - failure mode. It doesn't help you if the sensors feeding the device quit. Also, LCD backlights can definitely malfunction, and if they do, they don't fail in a way that a secondary display could detect. In addition to considering these "partial failure" scenarios, I also think the whole point of partial panel work is just to get the pilot used to the idea of using all available instrumentation to control the airplane when something goes wonky. It's not so much that you're trying to simulate a "realistic" failure, as it is that you want the pilot to be thinking about things like the fact that airspeed is a somewhat decent indicator of pitch (at a given power setting), GPS groundspeed is a somewhat decent indicator of airspeed, that a good old wet compass really does show heading, and that GPS track is a fine proxy for heading in all but the most extreme circumstances. That a standard rate turn as shown on an old TC really does change your heading 3 degrees per second, and so on. All of those things make you a better instrument pilot even in non-emergency situations, and the better you are individually, the better the system works for everyone. One of my airplane partners calls this sort of stuff "mental pushups", equating them to physical push-ups. We don't do push-ups because the push-up motion is something most of us often (or ever) need to do in real life. We do them because they help you be generally strong, and being generally strong is good for your overall health, even if the exercise that got you strong isn't directly applicable to your life. Once I started thinking of things this way, I got more creative about simulating failed equipment. Partly because it's fun and helps me learn more about the complex systems we fly these days. But also because it wholly and legitimately dismisses pointless fights over what is a "realistic" failure. The vast majority of pilots flying behind EFIS panels are - understandably - never going to be able to understand the nuances of all the possible failure modes. I can tell you that as a hardware/software engineer, even the people that design the systems can never completely guarantee they understand all the failure modes. If they can't, you can't. And if you can't, mental push-ups is the best strategy. But getting back to the original topic, this is not the sort of thing you knock out in a single IPC. Again, an instrument proficiency check is not instrument proficiency training.

-

In my experience that's not always practical. It's one thing to aggressively polish down a flat surface like a wing skin. Quite another if the stain has seeped into lap joints, non-flush rivets, and so forth. In those locations, you're likely not getting rid of the blue/brown stains without taking a wire brush down to bare metal and repainting a touch-up area. A combination of laziness and interest in preserving the protective value of the paint even if it looks awful, has left us with a number of blue/brown stains on the undersides of the wings. I'm watching these threads with great interest. We've been getting by with tolerating small seeps and making every-few-years patches on our original (1976) sealant. That got us through the ~20 years since we bought the airplane, and I don't regret the approach one bit. But the collection of small annoyances and increasing concern about getting to a patch facility in the event of a major breach, has led us to schedule our airplane with Don Maxwell for a full strip and reseal at the beginning of February. I'd like to think this is going to give us "new" sealant that's relatively impervious to whatever fuel achieves market leader status in the future, but time will tell. It's hard for me to worry about the paint for now, as the current paint job was not that great on day one (in 1990), and now has 35 years of wear-and-tear. G100UL is sort of a moot point for us in the near future, as there is none nearby: only 100LL at our home drome , and UL94 that we can't use at some other Colorado airports.

-

We did the light bulb thing for a while, but ultimately decided jamming a glass bulb in the engine compartment (even with the protection of a trouble light cage) skeeved us out. Now we put a small electric space heater under the cowl and direct the airflow up the cowl flap. It's not fast, but it's better than the light bulb, and seems less risky.

-

Uh... negative... multi-engine training aircraft do indeed spend a whole lot of time with the throttle pulled back and the prop windmilling. Almost all OEI training is done with the "dead" engine actually still operating - it's either windmilling at idle, or operating at a very low power setting ("zero thrust"), because it's considered good risk management to minimize the frequency and locations under which an engine is actually feathered for real. Power off stalls require a windmilling prop. Vmc demos require a windmilling prop. Emergency descents are always performed with both engines at full RPM and idle power, in a high speed descent. This sort of work happens every day, so it makes it hard to buy into the idea that prop-driving-the-engine is a high-risk concern (hard to worry about "shock cooling" too, but that's a separate subject). None of that takes away from your data point on your buddy's RV-6 with the broken rings, though. And again, the acute risks of multi-engine training are high enough that long-term engine management concerns might be dismissed even if they're real. I'm just trying to understand the physics.

-

That's exactly why I'm asking for details. I'm a relatively fresh multi-engine instructor. The nature of the training requires allowing the "prop to drive the engine" on essentially every flight. Nothing in any multi-engine training material I've ever read indicates this is a concern. To be fair, the concerns of an immediate emergency/loss of control/crash are so acute in that environment that probably no one worries about the longevity of the engine. A neuron fired, and I remembered this article from AvWeb a long time ago: https://www.avweb.com/features/pelicans-perch-78-props-driving-engines/. It seems to suggest that the issues with the location of the oil hole in the rod journals, torsional resonance, etc. are "real", but do not rise to the level of an operational concern except in radial-engine (master rod) powered airliners descending at very high speed out of the flight levels for very prolonged periods of time.

-

What, exactly, is the strain or wear mechanism in the prop/crankshaft train that makes this a concern?

-

Ballpark Fixed Costs when Doing Math for a Partnership

Vance Harral replied to bigmo's topic in General Mooney Talk

Thanks for the complements. I'm willing to share our documents, but I first owe my partners the courtesy of getting their consent to send them to third parties. I'll ping them when I get a chance, it will take a few days. One thing I will say immediately is that it took us a while, but we finally figured out that one should have one simple document which addresses the business of the LLC and its members only in general terms, independent of what business the LLC might be engaged in (things like how shares are tracked, rules for meetings, etc.); and a separate and usually more complicated agreement that details how aircraft owned by the LLC are operated, maintained, and funded. Don't mix and match the two, as doing so winds up creating conflicting information and generally just becomes a headache. -

Ballpark Fixed Costs when Doing Math for a Partnership

Vance Harral replied to bigmo's topic in General Mooney Talk

That's the way our partnership works, and I was really enamored of the idea in the early years. I'm not disenamored with it now, but I also don't care about it as much as I used to. It turns out it that people who spend a lot of time advocating for this kind of thing are largely missing the forest for the trees. The majority of fuel bought will always be at the home airport, because any other strategy quickly runs afoul of the hourly cost just to fly the airplane to the airport with cheap gas. So pilots are only going to leverage this delta on cross-country flights. A really active partnership (not a flight school) might have partners who each fly 100 hours per year at roughly 10GPH. That's 1000 gallons of fuel per partner, most of which will be bought at home. Even if a partner with particular wanderlust buys fully half their fuel away from home, and manages to save or spend an absurd average delta of $2 per gallon, the resultant "savings" or "subsidy" vs. other partners is $1000 in this extreme example, and in reality it's much less - maybe a few hundred bucks. Compared with the cost of owning and operating the airplane in the first place - especially the uncertainly discussed above - this just isn't a whole lot of scratch. That's not to say it's not still a good idea. But when forming a partnership, you really want to look for cues about whether the individuals are more concerned about the health of the partnership and friendships, or more concerned about "getting their fair share". People who put a lot of energy into arguing about how wet rates aren't fair tend to be in the latter category, though that's of course not an absolute. Just my two cents.