-

Posts

1,546 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

6

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Gallery

Downloads

Events

Store

Everything posted by Vance Harral

-

FYI, it's my understanding that Dan is no longer with LASAR. I'd be happy to be wrong about that if someone wants to correct me.

-

What kind of clouds do you refuse to enter? Poll

Vance Harral replied to 201er's topic in General Mooney Talk

Well, here's a real-time clip of what it looks like for me right now on an old Windows 10 laptop with 2.4 GHz WiFi and cable internet. Pretty snappy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kpPWpbeezz4 -

What kind of clouds do you refuse to enter? Poll

Vance Harral replied to 201er's topic in General Mooney Talk

Huh. I don't get that behavior at all, nor do a few others I've recommended the site to. Just tried it on my phone and it's snappy there too. May be specific to your combination of computer/browser/internet. But not accusing you of fibbing. I can tell just by the look of the thing that it's a resource intensive interface. I really liked the old rucsoundings.noaa.gov site. Kind of an old-fashioned interface, which is I suspect why they took it down. But it was simple to use. -

What kind of clouds do you refuse to enter? Poll

Vance Harral replied to 201er's topic in General Mooney Talk

FYI, https://sites.gsl.noaa.gov/desi/ seems to be the NOAA replacement for rucsoundings.noaa.gov. It didn't show up until a while after rucsoundings.noaa.gov disappeared, and it's not well advertised. But it looks to be an improved version of the same interface. Navigate to the site, then click the icon in the top right corner that looks like a little Skew-T plot. That will show you a plot near your geographical location, and from there you can select different locations and times. Once you've selected your favorite site, you can bookmark the lengthy URL that shows up in your browser and use the bookmark to navigate directly there the next time. -

Restore or remove Accu-Trak B11

Vance Harral replied to christaylor302's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

We have a fully working Brittain PC/B-5 system, and it's nice for what it is (75-year-old technology). But at this point, I think the question of resurrecting a non-working Brittain system has less to do with cost and workload - which are manageable - and more to do with the availability of mundane parts: vacuum lines, servo boots, etc. http://www.brittainautopilots.com/ is still online with a listed phone number, but it's my understanding that people who have recently tried to obtain parts either never get a response, or get a response that the company is "in limbo" with little or no legal ability to actually make parts. That leaves salvage items, kludge fixes, and under-the-table deals, which is a frustrating scenario for an aircraft owner. It is not difficult to debug why the system isn't working, but once you identify the problem(s), you may find it difficult to resolve them in a satisfactory manner. In our case, we have a small cache of spares, but maintaining the system has begun to feel more like maintaining a warbird than a certified airplane. -

Looking for RH brake pedals '77 M20J

Vance Harral replied to David M20J's topic in Modern Mooney Discussion

No, that's something I just wouldn't do - too much risk. In my case, it's easy to avoid that risk because I have instruction privileges at a local flight school. I can take anyone who is a truly green newbie over to the flight school and put them in the left seat of a 172, which is frankly a better Discovery Flight platform anyway. Over the course of a few flights at the flight school, I might build enough trust with them to get into a different airplane with only one set of brakes. But there is a lot more to that conversation than just the brakes, see below. This is a little awkwardly worded, not sure what you're asking here. I wouldn't hesitate to give instruction in a non-dual-brake Mooney to someone who already held a Private Pilot license. At that point it's reasonable to assume basic competency with the brakes, along with an understanding of the (rare) conditions under which they're needed. It's just transition training, a very common and reasonable operation. If you're talking about a student who is a post-solo but pre-private pilot, transitioning to a Mooney for the remainder of their training, whether or not the Mooney had dual brakes is the least interesting question about such a proposition. I'm not a naysayer about this sort of thing. One can absolutely train for the Private Pilot certificate in a Mooney, and in fact I'm familiar with a person who successfully earned his Private Pilot certificate in a turbo Mooney. But I declined to be involved with that operation for a couple of reasons. One is that it predictably took them a very long time to finish, working in fits and starts. It wound up being a multi-year effort, and to be honest that just didn't sound like any fun to me. More importantly, this person did all their training "naked", because they couldn't find anyone to insure the operation of a turbo Mooney by a student pilot. Even though I carry my own liability insurance for instruction in owner-flown aircraft, the details and dollar amounts just got too far above my comfort level, so I recommended they seek out someone else. Which they did. Another instructor I knew casually took on the training gig, and succeeded. Based on observing their success over time, I did agree to give the student a single "mock check ride" right before their practical test. But at that point, whether the aircraft had dual brakes (I don't even remember at this point) was irrelevant. A J model is less complicated than a K, and perhaps more reasonable for primary training. But I have no idea what the current insurance market looks like for that sort of thing. And whether I would take on such a gig would depend more on the person than on the airplane. In addition to physical and financial risk, I care about the likelihood of success, and whether it's going to be any fun for both of us; and training in an airplane that's not a trainer weighs on those goals to some degree, even if you think Mooneys are cool. I think people who point out in these sorts of threads that the military solos people in an 1100shp complex turbines, inappropriately gloss over the fact that doing so is a full time job for both instructor and student. Most civilian aircraft training is a weekend/afternoon hobby, and it doesn't take much additional overhead to make the hill of success too high to climb. -

Problem with Misc. Field displayed on my GI275/HSI

Vance Harral replied to NicoN's topic in Avionics/Panel Discussion

Sounds like a firmware update is the next thing to try if you're not on the latest version. Can't offer you much more in the way of suggestions - we're just lowly G5 consumers, I haven't tried to follow the GI-275 firmware versions. I'm not in the avionics business, but I am in the electronics business, and I have at least some sympathy for Garmin wanting most of their service business to work through shops with which they have an established relationship. Things do tend to go better that way for a collection of reasons. But anyone in this sort of business also understands that granting "authorized dealer" status doesn't make that specific shop a good resource vs. a skilled DIYer. Sorry you had a a mediocre experience with your last Garmin shop, but it's not particularly surprising. I recently had a bad experience with a "Mooney Service Center", so I feel your frustration. -

+20 year old donuts (1966 M20E)

Vance Harral replied to Matt Ward's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

True, but the thing that's killing people at the greatest rate has nothing to do with shock disks, or mechanical condition in general. The vast majority of maiming and death in the airplane world remains poor pilot technique (including me, I'm not immune). It would be an interesting world if people spent most of their "safety dollars" on actually flying the airplane and getting coaching from other experienced pilots (doesn't necessarily have to be an instructor). In the real world, $2400 shock disks often lead to less flying - particularly training - and that's a much higher risk than the condition of the shock disks themselves. That's my problem with this whole, "It costs what it costs." philosophy. No one's pocketbook is unlimited, but even if it was, safety isn't simply a function of maximizing how much time and money you spend on the mechanical maintenance of your airframe. -

Problem with Misc. Field displayed on my GI275/HSI

Vance Harral replied to NicoN's topic in Avionics/Panel Discussion

OK, the video makes it easier to understand your question. I'm not a GI-275 expert, but based on general principles I have two guesses. One is that it's a software issue as you speculate: either a bug, or a config setting that is so esoteric and convoluted it may as well be a bug. That seems the most likely cause, but you'd have to check with Garmin on that. My wild conspiracy theory involves the inputs an air data computer needs to compute winds aloft. Those are pitot pressure, static pressure, OAT, ground track, and ground velocity. To the best of my knowledge, each GI-275 receives these inputs "directly", meaning the HSI does not rely on the PFD to transmit them, but rather that it has it's own independent inputs (albeit ones which may be connected in parallel to the PFD). In the GI-275, the pitot and static pressure inputs come from actual pitot and static lines connected to the instrument. Everything else is electronic wiring. It's somewhat unlikely the electronic wiring of your HSI is compromised, as that's "all or nothing" data that would likely cause other problems you probably would have noticed. But I'm wondering if it's possible the pitot and/or static lines are slightly loose or slightly clogged, such that the air pressure data received by your HSI is erratic in a way that might cause certain air data functions to "go offline", particularly at low speed (i.e. on the ground). This would require a situation where the pressure lines are good enough not to generate red Xs, but not good enough for whatever code computes winds aloft. Seems very unlikely, but an easy experiment is to pull the breaker on the PFD in flight (on a good VFR day, obviously), and let the HSI revert to being a PFD. Then you can see if the airspeed an altitude on that unit are erratic in any way. If so, you might check the pitot and static connections to it. -

+20 year old donuts (1966 M20E)

Vance Harral replied to Matt Ward's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

If you read back through this thread, you'll see that @Gert did exactly that for his own purposes, and tried to help out other owners by making parts available at https://avunlimited.co/product/mooney-landing-gear-shock-disk/ There was some predictable skepticism about the degree to which this qualified as OPP, but I think most of the group here was enthusiastic and supportive. Response elsewhere (Facebook posts) was less kind. The parts on that web site have been listed as "out of stock" for years, and Gert hasn't visited this board in 3 years. I don't know what all may have gone on in the interim, but it renders me pessimistic that there's an OPP solution for the masses. Only, perhaps, one-off installations by individuals who stay quiet about it. -

+20 year old donuts (1966 M20E)

Vance Harral replied to Matt Ward's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

Correct. But the fix for that costs pennies in the way of O-rings, hydraulic fluid, and air; and it doesn't require special tools most shops don't have. Mooney "pucks" were a fine idea in their time, but the current state of the parts and service market makes them undesirable. Bonanza/Commanche/etc. owners aren't contemplating whether they should jack their aircraft up off the gear after every flight. Buy them now. They have a decent shelf life when stored indoors, uninstalled; and the price and availability are only going to get worse between now and when you need them. -

Problem with Misc. Field displayed on my GI275/HSI

Vance Harral replied to NicoN's topic in Avionics/Panel Discussion

Do you have a digital OAT probe system connected to your Garmin avionics, that along with pressure altitude allows the computation of true airspeed? Calculation of winds aloft requires knowing true airspeed in addition to GPS-derived ground speed. No digitally connected OAT probe, no winds aloft data. -

+20 year old donuts (1966 M20E)

Vance Harral replied to Matt Ward's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

This idea of jacking up your airplane while in the hangar has been discussed before, and I even know of one Mooney operator at my local airport who does it. But I find it ridiculous, and a good example of inappropriately de-emphasizing a significant risk to address a much less interesting/important risk. The risk of a Mooney falling off the jacks is pretty small if it's only done once per annual. It's significantly higher if you're doing it literally every time you fly the airplane. The cost of the airplane falling off the jacks would be 50x the cost of a set of gear pucks (for the average Mooney), not to mention weeks/months of repair time (or infinite if the aircraft is totaled). It requires extra equipment to maintain, extra procedures, and extra caution telling everyone who comes by your hangar to be careful and not lean on the airplane. On a lesser note, it makes you the laughing stock of the airport: "Haha... I guess those Mooneys are OK airplanes. But the landing gear design is so dumb that owners jack up their airplanes in the hangar". Overall, just a really bad idea. To each their own, but if this really became de rigueur for Mooney owners, I'd sell the airplane. -

Garwin Cluster Cylinder Temp Zero

Vance Harral replied to Mellow_Mooney's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

The OEM CHT probe on that vintage of Mooney is not a thermocouple. It's a thermistor, which works on a different principle, and uses the engine itself as the ground connection (hence why there is only one wire to the probe). CHT probes from JPI and Insight are 2-wire thermocouples, they simply don't work with the original CHT gauge in the Garwin cluster. That's the whole reason "piggyback" thermocouple probes are used when a non-primary engine monitor is installed in an aircraft which needs to retain the OEM CHT probe. It allows the original thermistor to stay installed to drive the original gauge. This is the CHT probe that fits our 1976 M20F: https://www.aircraftspruce.com/catalog/inpages/rochcht.php. Older M20F models may use the same one, but double-check your parts manual -

KOXR Mooney blade failure

Vance Harral replied to ragedracer1977's topic in Mooney Safety & Accident Discussion

This is a real concern, but like much of aviation lore, I think it's oversold vs. other concerns. Story time: we bought our M20F in 2004, with the Hartzell HC-C2YK-1BF common to that vintage. The prop was installed in 1991, and had never been overhauled at the time of our purchase. In the past 21 years we've had it overhauled twice, including the dreaded blade profiling. Once in 2006 when we installed a new "B" suffix hub to eliminate the prop AD. Again in 2016 because it was slinging grease, and the well-recommended local shop that allowed us to avoid shipping to other parts of the country declined to IRAN a prop with a little over a decade since the last overhaul. We're now at 34 years and counting on this set of prop blades, with two overhauls, and perhaps a third coming up in the next few years if we follow suit. The last time we had the prop overhauled, I asked the shop how many re-profiles they thought the blades had left in them. The answer was "definitely one more, likely two, maybe three if your really lucky". So we're on track to get 45+ years out of this set of blades (and I might be dead by then), despite ignoring advice to "never get a full overhaul if you don't absolutely have to". If we'd had the prop overhauled every 6 years as the manufacturer recommends, we might be at limits on the blades now; but maybe not - a competent shop only removes the minimum material required to re-establish the profile, and the less operational time on the prop (which correlates somewhat with calendar time), the less material removed. But even if we were forced into a new set of blades today, that would amortize the cost over 34 years, which is longer than most people own an airplane in the first place. Looks like our F7666 blades retail for about $9K apiece these days, $18K for a set. Nobody wants to write a check for $18K, of course; but in our case that would work out to about $500/year. Not exactly break-the-bank money in terms of multi-decade aircraft expense planning. None of this is to say that IRAN-instead-of-overhaul is a bad idea, and I acknowledge there are probably some incompetent shops out there that take way more material off a blade during overhaul than is necessary. But re-profiling is done for a reason, as are other operations required in a full overhaul, and those things do actually have nonzero value. Equally important, understand that if you have a prop that hasn't had been completely overhauled in a long time, a subset of prop shops - including some good ones - simply aren't going to IRAN it for "policy reasons" (that was the chief driver of our 2nd overhaul - the local shop was really convenient, competitively priced, and well-regarded, but they just weren't going to IRAN a 10-year old prop). There are plenty of shops with more liberal policies, of course, but they may not be in your local area and/or have the best rates, so that complicates the decision making. Bottom line: sure, get an IRAN and avoid profiling if you can, you won't get any criticism from me. But blade profiling is not the only concern, and it's not dumb to opt for a full overhaul. -

Yes. The approved model list is available at https://www.garmin.com/en-US/p/604257/#additional. The "201" is, in type certificate terminology, a Mooney M20J model.

-

I applaud the concept of personal minimums. But when I give my students the speech about them, I treat them like grownups, and explain that reality often makes it difficult to employ the concept the way it's written in the books. In fantasy land, one sets personal minimums for weather, pilot rest, and so forth, that start out very conservative, and are gradually stepped down as the pilot gains experience. This fantasy can actually work OK in reality if your life moves slowly, the frequency at which you fly changes smoothly, and the weather where you live is broadly varied. In reality, most of my students experience sporadic patterns. For the pilot, it's common to do a lot of flying in a short time, then have long layoffs when money or life work load gets in the way. Weather-wise, where I live, winds tend to be either mostly calm, or gusting 20+ with shear; and ceilings are either very high or very low. So this idea that you gradually push your minimums down (and up) with experience and currency, just doesn't work out in practice for me and my kin. Two specific examples that are common in my area illustrate the point. First, the idea that you can do something like step up your crosswind tolerance in increments by first flying on a day with 5 knots crosswind, then soon thereafter 7, then soon thereafter 10, and so on, is laughable - that just doesn't happen around here. The reality is that you have to set your sights directly on 15G25, and go out with an instructor on those days until you're willing to accept that level of risk by yourself (and we don't lie to ourselves - a 15G25 crosswind always adds risk to takeoff and landing no matter how comfortable and proficient you are). With regard to IFR minimums, there's very little flyable IMC on the front range of the Rockies where I live. The clouds almost always have ice in the winter, and convective activity in the summer, and they're rarely within 2000' of the ground. So you're not going to "ease down" your approach minimums from 1500' AGL to 1000' to 700' and so on. You practice those ILS/LPV's under the hood to 200' AGL as if your life depended on it (because it does). Then you go out on one of those rare flyable IMC days and shoot a low approach for real. People with real life work/family schedules around here actually get to fly IMC a couple of times a year, if they're lucky. But if you make it work, it becomes reasonable to take that trip to the coast where benign IMC is more common. In the end, I've come to feel the same way as @bigmo about it. I actually care less about the theoretical concept of holistic personal minimums for a complete flight, than I do about "outs". I tell my students it's OK to take off if they judge it reasonable to take off from the airport they're already sitting at, and if they can reasonably expect to return right back to that airport. That keeps them reasonably safe for the first 10 minutes of the flight. Everything after that is dynamic: if you don't like the winds at your destination (maybe the look of them while 100 miles away, or maybe an actual aborted approach when you get there), can you find winds that are less and/or more aligned with a runway somewhere else? Do you have the fuel to get there? If IMC, where is the nearest VFR, or at least the nearest 1000' ceiling? These things need to be re-assessed several times per hour while enroute, and - this is critical - you need to be fully willing to wind up somewhere other than your original destination, even if you have to pee in a bottle on the way there. I've come to feel that some of the most important items in my safety arsenal are a credit card, toothbrush, change of underwear, and my work-over-VPN laptop in my flight bag. Having that stuff with me on every flight makes it much easier to divert somewhere with favorable conditions and wait things out. It turns out to be really rare to actually do this. But it's only once I developed the mindset, that I began to truly feel like I was correctly managing risk while traveling GA.

-

Ice on the bottom of the wings. Go or no go?

Vance Harral replied to rwabdu's topic in General Mooney Talk

FAA: YoU mUsT rEmOvE eVeN tHe SlIgHtEsT tRaCe Of FrOsT fRoM tHe WiNgS Aircraft designers, paint shops, and mechanics: [hits bong], "Let's permanently install 10 square feet of rough skateboard tape on the wing roots" Intended tounge-in-cheek, of course, but it makes one think... -

While this is reasonable advice, I'm pleased to say the lead time on tank reseals isn't quite as bad as people seem to think, unless you're simply unwilling to have it done anywhere other than Weep No More in Willmar. Dmax is doing a strip-and-reseal on our airplane starting next week, via an appointment we booked in December; and this thread details a good experience by a Mooney owner at Wet Wingologists, who worked him in on one month's notice. Not disputing that Weep No More is the defacto standard, king of the hill and all that. But there are other choices with similar equipment, reputations and warranties, and much shorter lead times.

-

mats for protecting wing finish during fueling.

Vance Harral replied to Vance Harral's topic in General Mooney Talk

Hard to believe it's been almost 5 years since the beginning of this thread. Our partnership has been using the original silicone mat purchased by Paul the entire time, with no issues. My PIREP below should be taken with a grain of salt, though, as our paint was terrible 5 years ago, and remains terrible today. We're cheap that way. The mat does appear to wrinkle just a little if you spill more than a drop or two of 100LL on it, and I was originally concerned this meant the 100LL was attacking the material and would eventually degrade it. But if you simply wait for the fuel drips to evaporate, the mat goes back to its original shape, and there is no evidence of the material breaking down over the years. I've stopped worrying about it. Note that I have no data on G100UL, as we don't fly anywhere it's available at this time. I do wish the mat was just a little longer on the long side, because with the hole for the fuel port cut as close as is reasonable to one edge, it doesn't quite hang over the leading edge of the wing when placed. This means that while fueling, the fuel hose still rubs directly on the leading edge of the wing, unless you specifically support it with a second hand. But the hose itself is rubber (or some rubber-like compound), and seems unlikely to damage paint, even if you have a nice paint job. The mat definitely protects the wing against accidental dings with the fuel nozzle itself. My favorite thing about the mat is just that it provides a place to set the Shaw cap (with all its scrapey appendages) while fueling. I no longer worry about it sliding off in a breeze or after being bumped, and further scraping up our dime store paint job. Worth it for that alone. As for Paul, I've visited with him recently, and he's well as you might expect. I helped him get a commercial certificate, CFI, and multi rating over the past few years. He recently sold his 252, and is on to other flying adventures, with two taildraggers in his hangar. He's actively using his certificates to teach and ferry airplanes, and I suspect he'll always be involved with the Mooney community, despite (for now) not being a Mooney owner. -

Another Lead (and noise) lawsuit - KAWO Arlington, WA

Vance Harral replied to Igor_U's topic in Miscellaneous Aviation Talk

Yes, and this same problem impacts pig farms, gun ranges, racetracks, and the like. I've been talking with friends about this a lot lately due to similar attacks on airports/operators in our own metro area. The bottom line is that, for better or worse, a large contingent of the population wants to live (and work) just far enough outside downtown to be "country", but not so far that it's more than a short drive to the grocery store, the doctor, etc. The sweet spot where you can do that spreads out every 5-10 years in any town or city that's not actively dying. So until the population collapses and/or literally all the land in the country is developed, airports and things like them are always, eventually going to be at risk from suburbanites. To keep your airport, you've got to convince the population growing around it that it benefits them, at least indirectly. The good news is, that's easier to do that with an airport than it is with a racetrack or gun range. The bad news is, as a group, pilots are pretty terrible at it. Far too much time and energy is wasted on pointless whining that, "The airport was here first". The reason this argument is dumb is that it's easily defeated - the pendulum will swing as soon as some reasonably intelligent person argues, "Yes, we agree the airport was here first, but the majority of our citizens don't care. Just because our community wanted an airport in the 1950s doesn't mean we want one now. Let's talk about the future, not the past, and that future is best for our citizens if the airport is closed." If you want to beat that, you've got to focus on why the airport benefits the town, not on childish prior possession arguments that just enrage the public and provide fodder for politicians. -

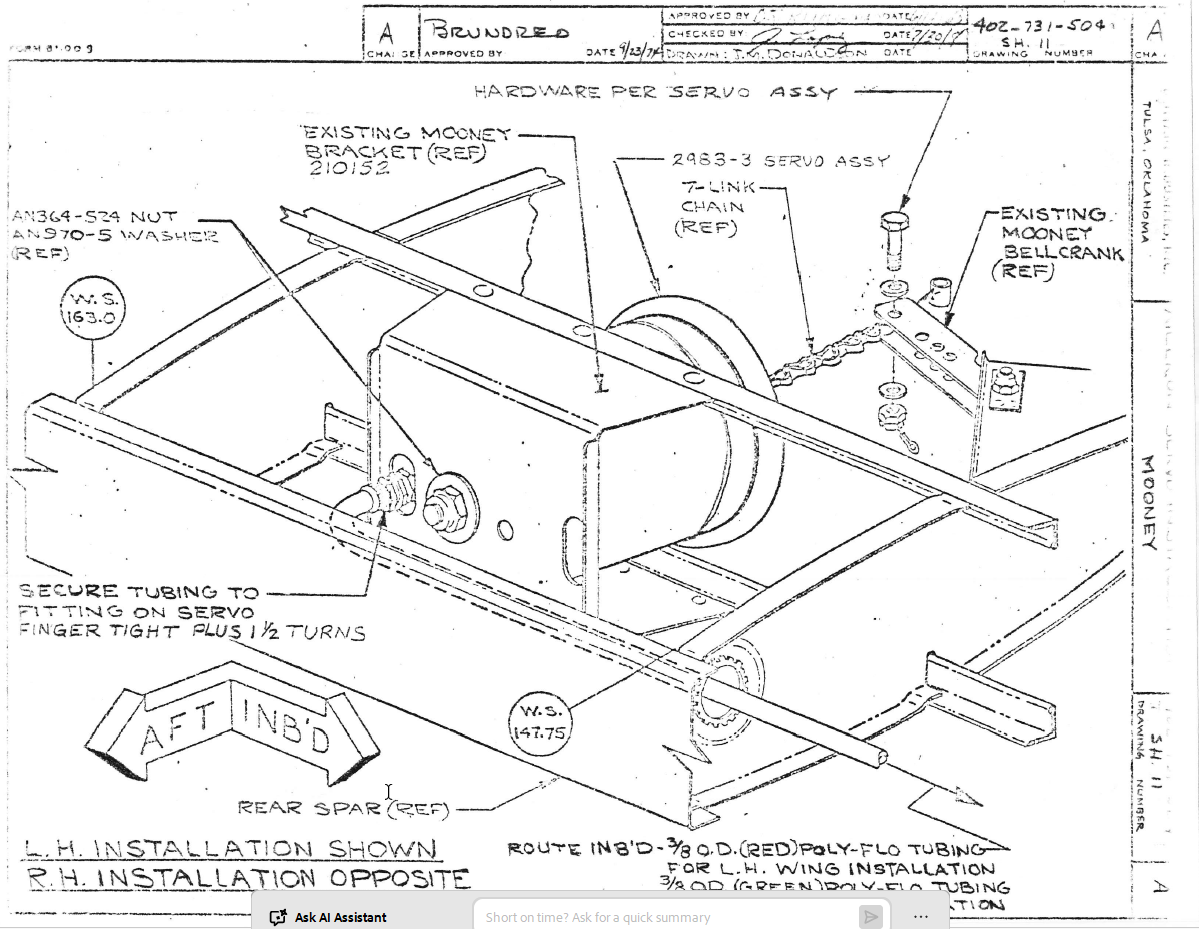

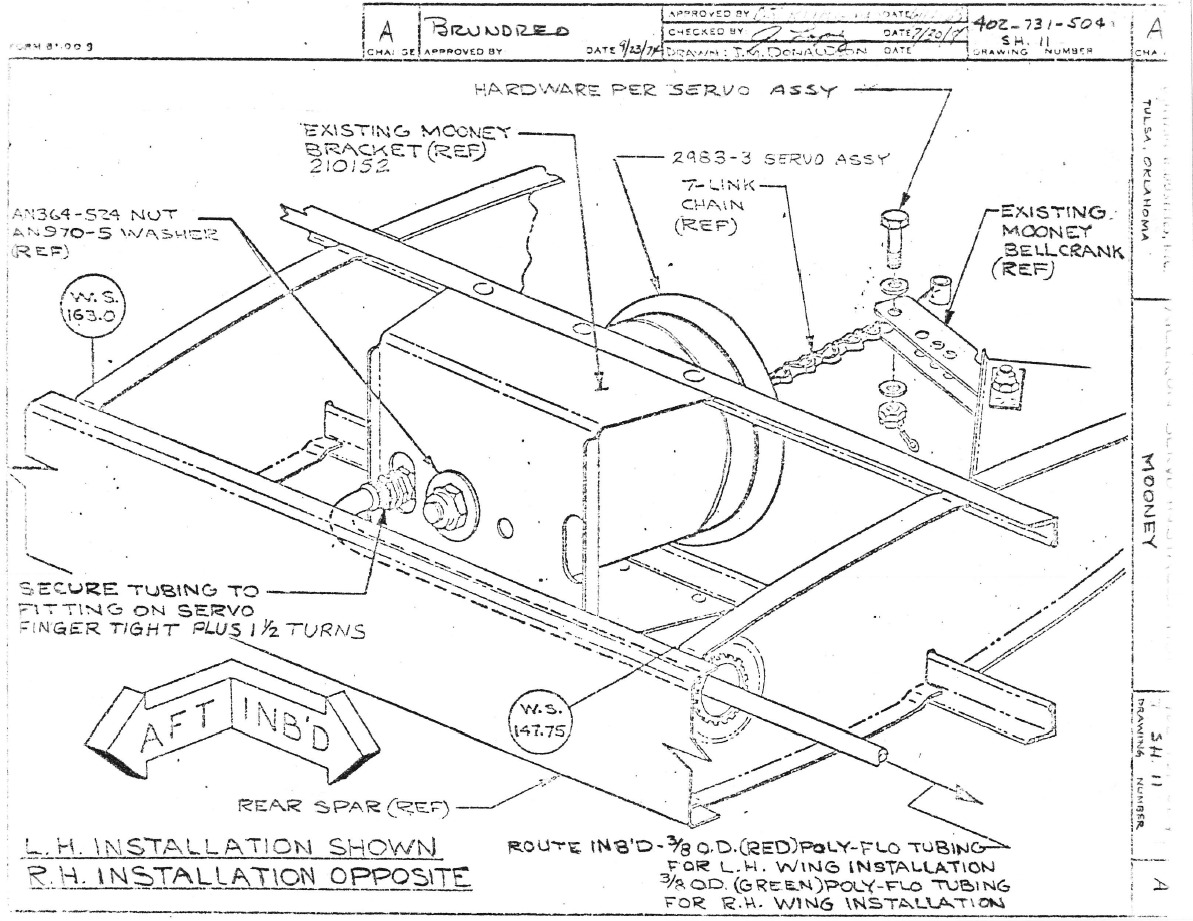

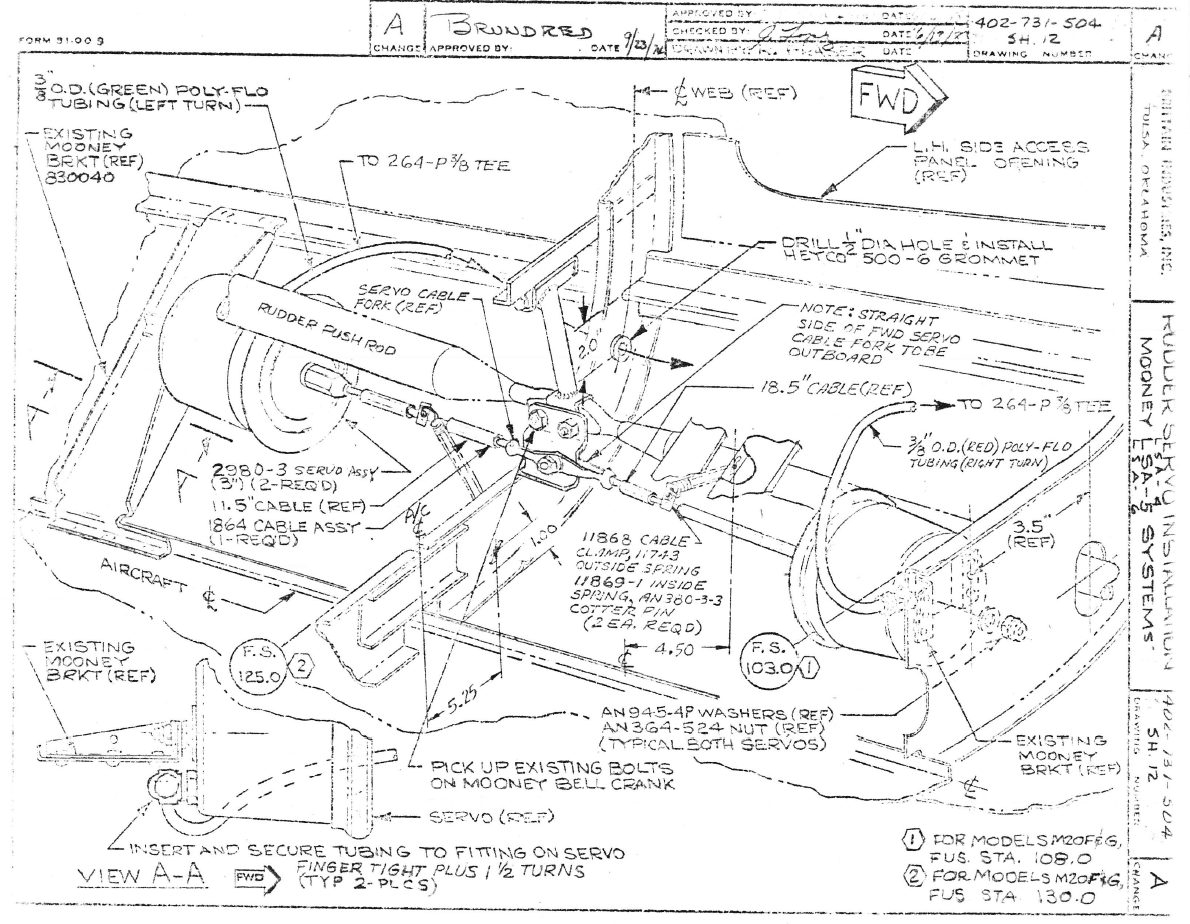

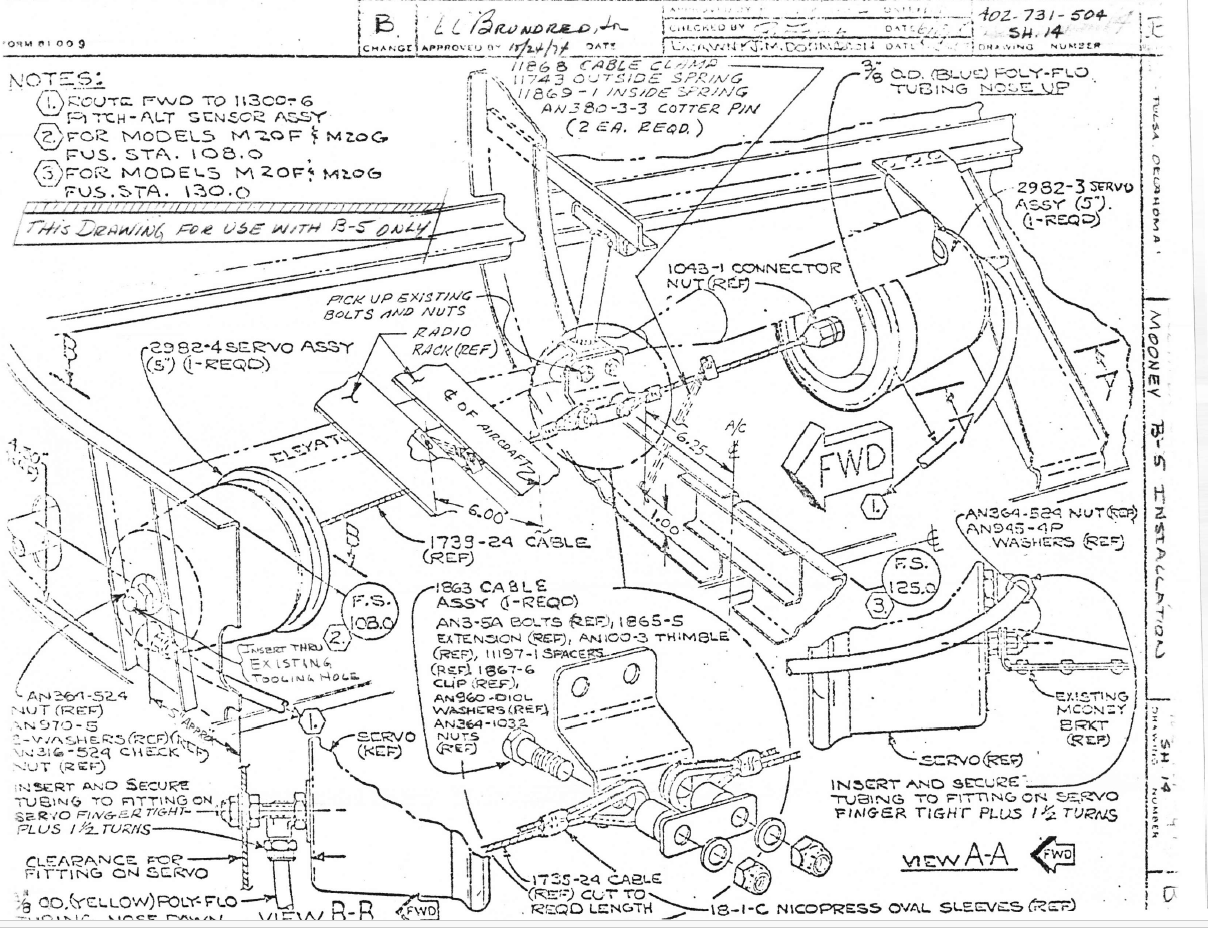

Below are screen shots of the Brittain installation manual for the various autopilot systems. Assuming your airplane is in the listed serial number set, the pages I've pasted have part numbers for the aileron, rudder, and elevator servos, respectively. As you probably know, Brittain is no longer in business, and to my knowledge no one is officially producing parts or overhauling servos. You'll have to look for salvage parts, a new-old-stock "barn find", or mount a repair campaign you and your A&P are legally comfortable with.

-

The M20F Performance Benchmark thread.

Vance Harral replied to Shadrach's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

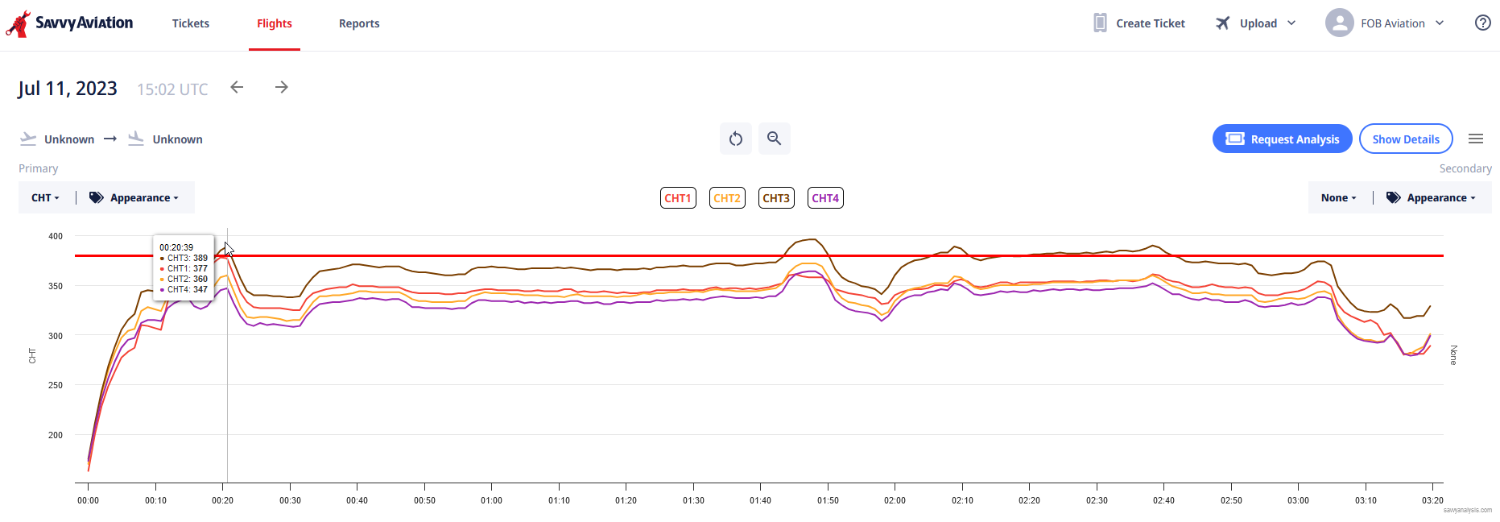

I live in the Denver Metro area and trek down to the Springs several times a year to go to the Airplane Restaurant for $100 hamburgers. We download and keep our engine monitor data, so I've got plenty of info on this. I went back 3 years and tried to find the absolute hottest day on which I or one of my partners had a recorded flight, correlating temps from https://www.wunderground.com/. The plot below is from July 11, 2023, when the high at KBJC (elevation 5673') was 95 degrees F. It's a long flight, and while we didn't have altitude recording at the time, it's essentially guaranteed by the length of the flight that the climb out was to 3000' AGL or higher. I'm not claiming the flight departed at the hottest point of the day, but it was obviously hot all day long. Hottest CHT in the initial climb peaks at 389F before quickly settling down at level-off. A later climb at higher altitude gets right to 400, again before quickly settling down. I also pulled the raw data from the CSV files over the past two years and sorted it. The highest CHT we've ever recorded on any day under any conditions in those two years is 413F. We've had all-cylinder CHT monitoring since 2006, and in all that time I've never seen anything remotely approaching 450. If you're confident your instrumentation is good and all your baffling is pristine, then the only thing I can think of is you're developing more power than stock, and/or your cylinders run hot (are they chrome perchance?) -

The M20F Performance Benchmark thread.

Vance Harral replied to Shadrach's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

I'm sure you're not, but either your instrumentation or your engine or your baffling is amiss somehow. There's no way a stock M20F departing from a Colorado airport should have any cylinder at 450F during a Vy climb, regardless of atmospheric conditions or where the mixture is set. On the very warmest days in summer, our engine might be a few degrees over 400, briefly. I've never seen anything remotely close to the factory redline of 460 in our airplane, or other E/F models I've flown in around here, for 20+ years. -

The M20F Performance Benchmark thread.

Vance Harral replied to Shadrach's topic in Vintage Mooneys (pre-J models)

Nah, not with a correctly functioning engine at high DA. That chart I posted shows the effect of CHT with leaning, it changes by about 10C (roughly 20F) across the "max power" band of mixture settings. A difference of 20 degrees CHT during initial climbout isn't going to destroy a correctly functioning Lycoming, particularly not on departure from a high DA airport in a normally aspirated airplane where you're making considerably less than the full 200hp. If your stock M20F hits 450F CHT during climb out from a 5000' airport - even in the middle of summer - the mixture setting is not the problem. Something is seriously wrong with the engine or the baffling. That doesn't make the target EGT method "wrong", but I think you're over-emphasizing the importance of it on takeoff. It's not a critical number on the takeoff roll or the first 1000' of climb, and it's therefore arguable whether it's worth the distraction of looking at it during a critical phase of flight. It's not so much that it's a huge risk to take a glance, and maybe even tweak the mixture knob based on what you see. But doing so doesn't result in a meaningful difference in performance or safety, so why bother? Ignoring EGT details during this time gives you a few more seconds and neurons to look at things that matter more - like the actual CHTs, which could be the earliest indicators of a problem unrelated to mixture setting, and therefore should be monitored anyway (along with oil pressure and temp). You can glance at the EGT and make a mixture tweak later, at 1000' AGL and about every 1000' thereafter.